Understanding Michael Porter, by Joan Magretta

My detailed notes on this incredible distillation of the work of the true leader of business strategy (and original author of Five Forces analysis), Michael Porter.

Wow. This book has quickly rocketed up the top of my list of all-time favorite reads on business strategy.

We often think we know what terms like “competitive advantage” or “differentiation mean, but I was frequently surprised at how incomplete my own understanding was. Magretta, clearly an amazing editor and educator herself, goes straight to the heart of these common misunderstandings with each chapter, complete with excellent real-world (and time-tested) examples of excellent strategy.

Understanding Michael Porter pairs well with Good Strategy Bad Strategy (which I think does an excellent and important job of exploring the fascinating self-sustaining logic of bad strategy), as well as 7 Powers (which I think does an excellent job at revealing the different unique sources of competitive advantage). In contrast to these, Understanding Michael Porter, with its unique takes on value chain analysis (chapters 3 & 4) and activity system mapping (chapter 6) provides a more action-oriented starting point for teams seeking to understand how they are (or should be more) unique.

Fantastic book, and definitely deserves a copy on any serious business leader’s bookshelf. Buy it. (Amazon, Bookshop).

Introduction

This is a distillation of Porter’s work (done in collaboration with him) on how to think about strategy; it does not cover how to craft a good strategy. To go beyond this starting point, invest in reading Competitive Strategy (1980) and Competitive Advantage (1985).

The value of Porter’s work lies in frameworks which balance abstract theory and messy practice. These frameworks describe the fundamental and unchanging relationships that govern business success in a given industry, and are not subject to managerial fads.

PART ONE: WHAT IS COMPETITION?

This section explains how to think about competition. It requires a) the right mindset (seeking to create unique value rather than beating rivals); b) the right analytics (understanding the structure of the industry and the company's relative position within the industry).

Chapter 1: Competition: The Right Mindset

Cultivate a mindset of being unique, not being the best (and undifferentiated). The sole purpose of strategy is to explain "how an organization, faced with competition, will achieve superior performance [on an ongoing basis.]" True success comes from creating unique value for customers: unique from what rivals offer, and valuable in the customer’s actual circumstances. When competing, focus on: a) earning higher returns (not being the biggest); b) profits (not market share); c) innovation (instead of imitation); and d) meeting the diverse needs of target customers. Some tips:

Avoid striving to be the best, which pits you against others in a zero-sum battle for the same customers and profits. This is a mistake, encouraged by vivid metaphors from war and sports.

Industries are complex and open-ended, and there can be multiple contests and winners based on whose needs are to be served.

Competing to be the best leads to a) convergence on the same commodified offerings; eroded profits due to continuous one-upmanship; reduced choice for customers; and stifled innovation.

Competing to be the biggest often leads to unprofitable mergers, damaging price cuts, and overextending your team. (“Big enough” is ~10% of the market)

Limited choice for customers typically means value destruction, either by being over or under served by available products.

Better metaphor: competing on unique value is like the performing arts; there are many good singers and actors, each distinctive, and they have their own audience.

Good choices in an industry “promote healthy competition, innovation, and growth. Bad choices unleash a race to the bottom.”

Chapter 2: The Five Forces: Competing for Profits

The point of competition within business is to earn profits, which is why it’s critical to understand how all players within an industry are positioned to capture the value created by the industry. Seek only to beat rivals is myopic. Porter’s Five Forces framework describes the following fundamental factors:

Intensity of rivalry among existing competitors: Occurs across different dimensions (advertising, price, features). Companies risk "competing away the value they create." Magnified when: a) no industry leader enforcing practices across the whole industry; b) slow market growth prompting battles over market share; c) presence of excess capacity and high exit barriers; or d) irrational commitment to the business. Avoid price competition (common with products that are undistinguished, perishable, or low marginal cost.)

Bargaining power of buyers: For example, Walmart in many CPG industries. Magnified when buyers are price sensitive, typically with undifferentiated products that are expensive relative to other costs, and/or inconsequential to their own performance.

Bargaining power of suppliers: Occurs across all dimensions of purchased inputs, including labor. Magnified when: a) large/concentrated compared to a fragmented industry; b) needed by the industry more than the reverse (e.g. neodymium for electric motors); c) switching costs are powerful; d) differentiation works in their favor; and e) they “can credibly threaten to vertically integrate into producing the industry's product itself."

Threat of substitutes: Caps overall industry profitability; if prices rise too high demand will shift to substitutes. Potential source of widespread disruption when substitutes get less expensive (e.g. consider the impact of widespread electric car adoption). Switching costs & ingrained habits play a significant role.

Threat of new entrants: Influenced by barriers to entry. Different types: a) true economies of scale giving large incumbents lower unit costs; b) supplier switching costs; c) network effects accrued by existing players (more people using a given supplier may increase customer value or perceived "safety"); d) required capital investments for someone to enter the business; e) other incumbent advantages such as IP, brand recognition, access to distribution channels, etc. f) governmental policies restricting or preventing new entrants; g) expected retaliation from incumbents when a new entrant joins.

These five are the fundamental forces relevant to every industry. The industry structure they reflect is surprisingly stable, once beyond the emerging prestructure phase. Each factor systematically influences profitability in predictable ways, albeit in varying degrees for each unique industry. Further notes:

New products or technologies usually change industry structure quite little.

The relative power of any given force corresponds to the pressure it places on prices or costs or both. Industries with powerful forces are (generally) less attractive to incumbents.

Many other factors are important, but mainly act on an industry through one of the five forces: a) government regulation (e.g. may prevent new entrants); b) technology (e.g. may increase power of buyers); c) industry growth rate; d) complements (e.g. influencing demand)

Analyzing your industry structure is the best way to understand the lay of the land and identify the elements which deserve close attention. Expect this to be dynamic, as the relative power of the forces will change (possibly in response to your own strategy). General steps to follow:

Define the relevant industry, using product and/or geographic scope. Define separate industries when there are significant differences in more than one force.

Identify the key players for each of the five forces. If useful, group by shared qualities.

Assess the underlying drivers of each force; identify which are strong or weak.

Run a sense check based on available data. Does your analysis explain why certain companies are more profitable than others? Does it highlight which factors are most important?

Look for recent and likely future changes: Which factors are stable? Which are likely to change?

Identify ways you can position yourself within the industry structure. Which areas are weakest?

As Porter summarizes perfectly: “Good strategies are like shelters in a storm. Five forces analysis will give you a weather forecast."

Chapter 3: Competitive Advantage: The Value Chain and Your P&L

You only have true competitive advantage if you have superior (and sustainably higher than average) financial performance, generally by commanding a premium price, having lower costs, or both. Competitive advantage is cultivated through the specific activities you perform, referred to as the value chain, which add value to your product. Some tips:

There is no absolute benchmark of “superior” financial performance; this is relative to rivals.

One comprehensive measure is return on invested capital, which shows how effectively & sustainably you are using resources. (Avoid using growth rate or stock price as indicators).

Premium prices are sustained by offering unique and compelling buyer value, e.g. from increased convenience, better reliability, status conferred. Differentiation, per Porter, "refers to the ability to charge a higher relative price," not from simply having a different product.

Lower costs are sustained by inventing more efficient ways to offer your product or service, typically involving tightly coordinated aspects across the whole company. [Example: Dell’s tightly managed supply chain of outsourced components + customers paying upfront for computers.]

What matters is the relative spread between costs and price; any increase in your relative costs should lead to a larger increase in the price you can command (and vice versa).

The activities which comprise a value chain must be tangible and "discrete economic functions or processes, such as managing a supply chain, operating a sales force, developing products, or delivering them to the customer." An activity must add value. Functional areas (like marketing) are too abstract; specific “skills” (things your company is good at) also don’t count.

A value system encompasses the holistic set of activities done by all players to ultimately create value for the end user. It’s critical to understand your chain of dependencies with other players.

Operational effectiveness is not a sustainable source of competitive advantage because best practices are often copied quickly. It’s not enough to perform the same activities as your rivals only more efficiently; your fundamental activities must be different.

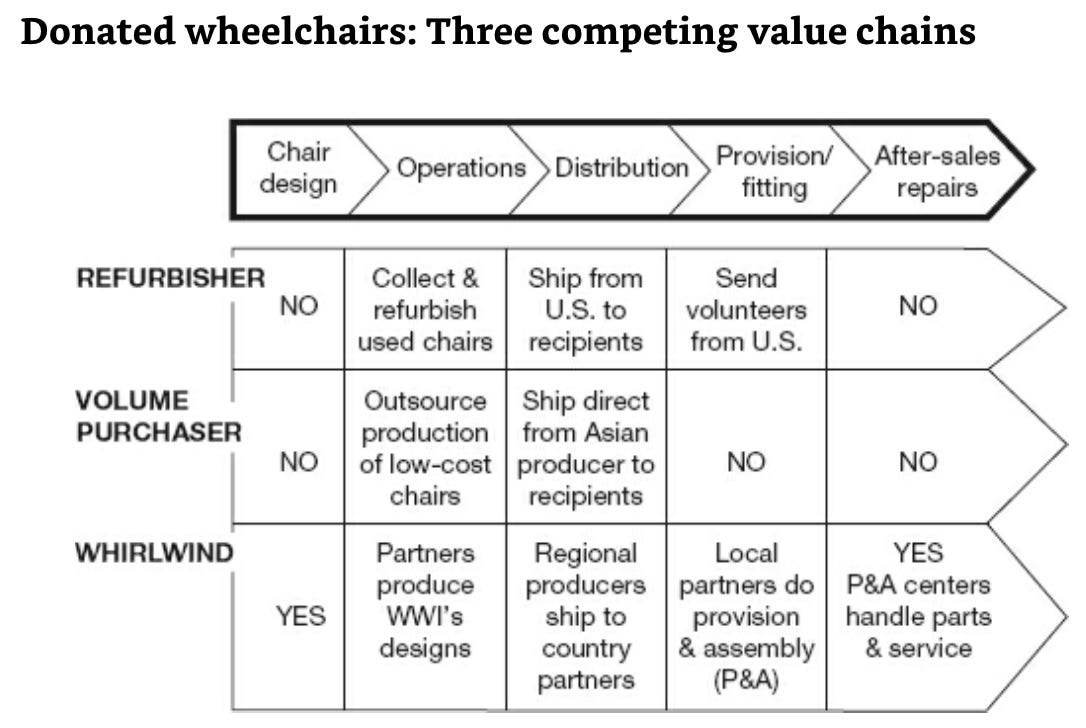

Conduct a value chain analysis and identify the strategically relevant activities for your company. This then helps to shape your strategy, which ultimately describes how competitive advantage is won or lost within an industry. Steps (with an illustrative example from the book):

Map the basic value chain steps for your industry. Identify the dominant (generic) approach. Capture the whole range of typical activities, whether including basic research, designing & developing products, etc.

Map your value chain alongside a few other key rivals.

Focus on price drivers, activities which impact differentiation. How can you create unique buyer value by doing things differently than others?

Focus on cost drivers, activities that constitute a large percentage of costs. Build a precise understanding of the full cost of each activity, and dig deep for actions you can take to reduce costs. Prompt for cost analysis: What would you save if you stopped this activity?

General rule of analysis: “Be brutally honest about the true profits you’ve earned and all the capital you’ve committed to the business. [...] The overwhelming tendency in organizations is to make results look as good as you possibly can."

PART II: WHAT IS STRATEGY?

This section describes how to distinguish a good strategy from a bad one. Behind each of the five tests (distinctive value proposition, tailored value chain, strategic trade-offs, fit across activities, and stability over time) are fundamental principles behind creating and sustaining competitive advantage.

Chapter 4: Creating Value: The Core

First two tests of good strategy: a) you must have a distinctive value proposition that is b) supported by a distinctive value chain tailored for your value proposition. You must deliberately choose “a different set of activities [from those of your rivals] to deliver a unique mix of value,” otherwise you’re competing to be the best (and not competing on strategy). Ultimately, strategy integrates the demand side (what customers care about) and the supply side (the value chain executed internally). Some tips:

A value chain that can support multiple value propositions is likely not tailored enough to maximize value. Likewise, you want a value proposition that requires a tailored value chain to deliver well.

You can be differentiated (commanding a premium price) and low cost at the same time. Customers' needs are multi-dimensional, and tailored strategies can be too.

New product extensions must be rooted in the unique strengths you have in your value chain. [Grace Manufacturing, leveraging their ability to create sharp things, created the Microplane.]

A well framed value proposition will answer three main questions. Note that any given value proposition may lean more heavily on one of these dimensions as a core which then defines others:

Which customers do you serve? Choose the customer segment that will position you in the industry, either via geography (Walmart's targeting of isolated rural towns), demographics, psychographics, or more.

Which needs do you meet? Importantly, this should not be “all of them” but must be specific. Sometimes, common need(s) shared at a given time may drive customer segmentation.

What price do you charge? This can be a primary leg in industries where customers are underserved (underpriced) or overserved (overpriced) by incumbents

As Magretta succinctly summarizes: "By definition, strategy is about creating something unique, making a set of choices that nobody else has made."

Selection of the rich examples shared in the chapter (including Enterprise, in image):

Walmart focused initially on offering “everyday low prices” to isolated rural towns; they used geography to insulate themselves from competition for years.

Progressive served higher-risk customers by developing risk assessment models tailored for finding lower risk pockets of customers within higher risk groups.

Southwest anchored their value proposition to low fares, serving customers who were overserved by the prevailing airlines in certain ways.

Aravind Eye Hospital delivers world-class surgical care to both a) patients who can pay market rates; and b) patients whose free care is subsidized by those who pay. All aspects of care are streamlined so that surgeons (their true rate-limiting factor) move seamlessly between patients.

Chapter 5: Trade-offs: The Linchpin

Third test of good strategy: you must make different trade-offs than your rivals. Trade-offs arise due to a) certain features being incompatible (large stores make quick in-and-out purchases difficult); b) certain activities being incompatible (plants designed for large production runs make small custom runs difficult); and c) inconsistencies in image or reputation (imagine Ferrari selling a minivan).

Avoid the tempting belief that "more is better" or that you can do both A and B (even when they're incompatible or end up canceling each other out). Make "fork in the road" decisions.

Avoid offering something for everyone; avoiding trade-offs weakens competitive advantage.

Improving quality through operational effectiveness (e.g. limiting defects and waste) is always important and should not be considered a tradeoff. Improving quality through premium features, better materials, or improved service is not free and requires tradeoffs to be made.

Features are easy for rivals to copy; trade-offs are hard to copy without paying an economic penalty. E.g. McDonald’s adopting customized orders diluted their strengths of speed and consistency and led to expensive upgrades, increased labor costs, and slowed service.

Straddling is competitive imitation that "tries to match the benefits of the successful position while at the same time maintaining its existing position.” Avoid this!

Often the hardest part is sticking to the decisions of what not to do. Any organization "that has sustained its competitive advantage over a period of many years [...] has defended its key trade-offs against numerous onslaughts."

As Magretta perfectly captures: "Trade-offs are essential in making what you do unique. Maintaining and steepening trade-offs, making them even sharper, is essential to sustaining strategy." You must choose what not to do.

Selection of the rich examples shared in the chapter:

TSMC chose not to design their own chips, which created competitive advantage in that smaller design companies were confident their designs would not be stolen.

IKEA makes a lot of tradeoffs to serve customers with "thin wallets," from internal product design having using sale price as a constraint, to flat-pack, to customers doing their own delivery & assembly, substituting in-store service with full room displays, etc.

Chapter 6: Fit: The Amplifier

Fourth test of good strategy: you must have fit across your entire value chain, where your activities and trade-offs are interdependent and deeply connected to the point where the relative “value or cost of a given activity is affected by the way other activities are performed.” When elements fit, they amplify each other and make it harder for a rival to imitate what you do. When elements don't fit, they work against each other or even cancel each other out. Some tips:

Your true unique value comes from the interconnected web of complementary activities.

Three types of fit: a) basic consistency across activities (e.g. aligned with the dominant themes of the company's value proposition); b) activities complement or reinforce each other; or c) being able to entirely substitute one activity for another (e.g. Dell collaborates with suppliers and customers to load customized software onto new PCs during the assembly process, saving customers significant time and money.)

Example of lack of fit: when manufacturing is tasked with reducing costs while sales is encouraged to book custom orders, leading to conflict.

Avoid outsourcing any activities except those which are entirely generic in nature. "The fewer elements that remain in the company's value chain, the fewer the opportunities to extend tailoring, trade-offs, and fit."

Use your activity map (see next) to root out inconsistencies, strengthen fit, and even find new ways to leverage your unique activity system.

Create an activity system map to chart a company's significant activities [and] their relationship to the value proposition and to each other." Steps: a) identify the most distinctive aspects of the value proposition (large circles); b) identify the most relevant & unique activities responsible for creating customer value or generating significant cost (small circles); then arrange them on a map and draw lines where they either contribute to one of the value propositions or affect each other. The more dense & tangled the web is, the better. [See examples from Zara.]

As Porter summarizes, “Fit locks out imitators by creating a chain that is as strong as its strongest link.”

Selection of the rich examples shared in the chapter:

IKEA’s use of flat packs both reduces shipping costs and also allows customers to take the items home in their car today rather than waiting for delivery.

Zara’s speed-optimized supply chain (clothes are delivered already pressed and on hangers) relies on window displays in expensive, high-foot-traffic locations, substituting for advertising.

Chapter 7: Continuity: The Enabler

Fifth test of good strategy: you must have continuity over time, otherwise the tailoring, trade-offs, and fit don't have the time to fully develop. There is risk in changing too much, too rapidly, and in the wrong ways, so avoid the motivational call of "constant reinvention." Some tips:

Continuity unlocks competitive advantage by: a) reinforcing the company's identity & brand; b) creating space for suppliers & others to contribute in a meaningful way; c) fostering innovation within and between activities (especially since team members ‘get it’ and have the context they need to make good “decisions that reinforce and extend the strategy”

Frequent large shifts in strategy carry a heavy penalty. New strategies take years to implement.

Focus on reinventing how you deliver your core value to customers; stability in your strategy is not the same as standing still.

"Great strategies are rarely, if ever, built on a particularly detailed or concrete prediction of the future." Bet instead on a broad sense for what customers will reliably need in 5-10 years.

Avoid substituting flexibility for strategy; it's a great way to stay mediocre at what you do.

Still, make sure to pay attention to signs your strategy may need to change: a) shift in customer needs makes your core value proposition obsolete (e.g. Liz Claiborne’s initial success was built around women newly entering the workforce); b) innovations which invalidate essential trade-offs on which your strategy relies (e.g. Dell's cost advantage was wiped out by the emergence of Taiwanese original design manufacturers); or c) a disruptive technology or managerial approach that completely displaces the existing value proposition (e.g. Kodak and digital cameras; disruption is relatively rare). Tips on change:

Separate from strategy, make sure you stay at the cutting edge of organizational effectiveness, assimilating the "best practices that do not conflict with your strategy or the trade-offs essential to it." If you don't keep up, the costs may drown out your other advantages.

Seek out “ways to extend your value proposition or better ways to deliver it" and grow accordingly. For Netflix, the value proposition of delivering DVDs to your home is very aligned with streaming a video directly to your home device.

Great strategies take time to evolve, even while they stay true to the core principles that may have been the foundation for their start. It requires work, thoughtful design, rigorous analysis, trial & error, and willingness to continue exploring to discover what truly works.

Pay attention to what amplifies vs. diminishes the overall value you can offer to others.

As Magretta sums up: "Paradoxically, continuity of strategy actually improves an organization’s ability to adapt to changes and to innovate," and doing so prevents you from the whiplash of jumping on every new innovation that comes along. Offering your team continuity is even more important during periods of change and uncertainty.