7 Powers, by Hamilton Helmer

My comprehensive summary of Helmer's book, which offers a succinct and powerful framework for understanding business strategy.

7 Powers offers a succinct & powerful framework for understanding the “only worthy destinations” for a business seeking to create enduring value. Helmer dives into detail about the benefits & barriers enabled by each power, and explains how and when to create each of the types. This is a useful set of prompts for anyone seeking to develop their own business strategy or understand that of another company.

If you enjoy my summary below, I highly recommend buying and reading the full book either via Bookshop or Amazon.

Introduction

A good strategy (or strategic framework) is simple without being simplistic, and sets you up to take advantage of "high flux" moments that lead to outsized payoffs for your company. Strategy is about understanding what determines potential business value (both having value and creating that value, which the author refers to as statics and dynamics respectively).

Power is the most fundamental determinant of success, and is "the set of conditions creating the potential for persistent differential returns." Persistent = ongoing and defensible. Differential = you earn more than your competition in some way.

Put together: "Strategy is the route to continuing Power in significant markets." In equation form: [Potential Value] = [Market Scale] * [Power]. Market scale is a function of the current market size and the market growth (which makes it significant). Power is the function of long term market share and long-term differential margin, or "net profit margin in excess of that needed to cover the cost of capital."

“Armed with one or more of these power types, your business is ideally positioned to become a durable cash-generator, despite the best efforts of competitors. If you possess none of these, your business is at risk.” Treat each of these as the only worthwhile destination(s) for a lasting business.

PART I: STRATEGY STATICS

[The following reference charts are built up chapter-by-chapter through Part 1.]

The benefits and barriers of the 7 Powers are mapped out in Figure 7.6.

Key benefits are that either the power holder has an advantage in costs or an advantage in value offered to customers.

Key barriers are factors that lead the company not in power either to be unwilling to challenge or unable to challenge.

Hysteresis = a long period of reinforcing actions

Fiat = not based on ongoing interaction but rather comes by decree, general or personal.

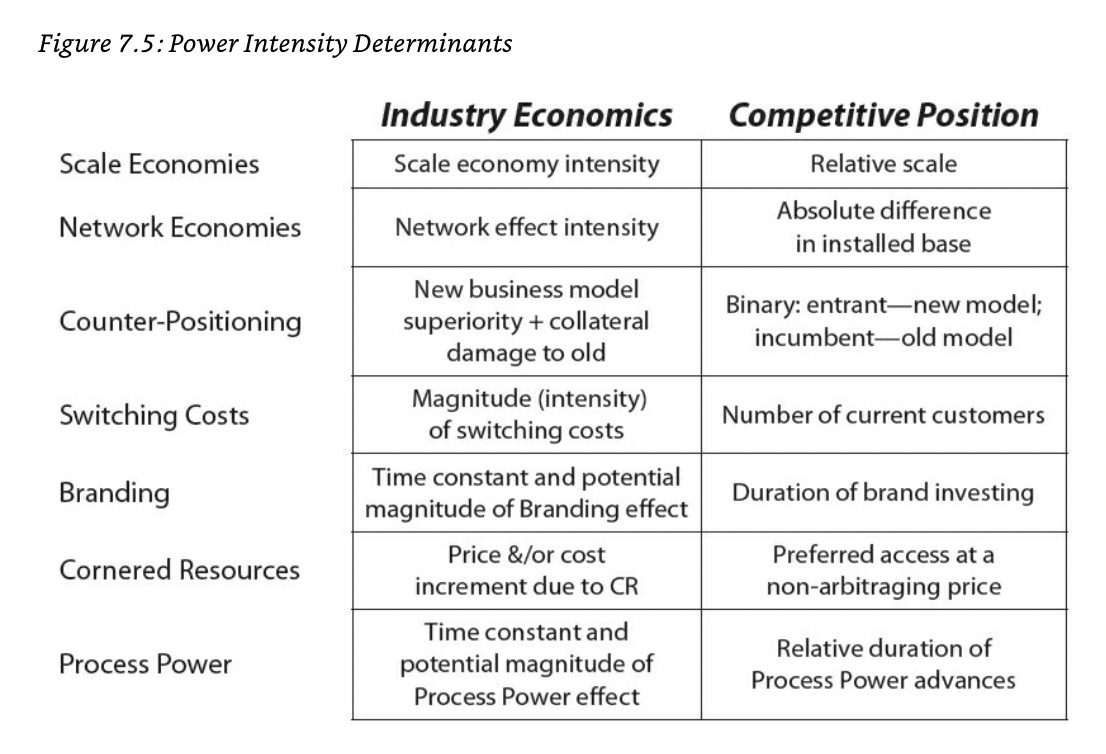

The industry & competitive determinants of power intensity are mapped out in Figure 7.5 for each of the 7 Powers.

Chapter 1: Scale Economies

You have scale economies when the per-unit costs declines as production volume (or your business) increases . E.g. Netflix has power if they can "distribute" the cost of a new program over 30M subscribers versus a competitor's 1M subscribers, which is a clear benefit. Netflix therefore has power to meet and beat any purely cost-based competition orchestrated to pick up market share. This also happens with: warehouses (larger = lower per-volume costs); distribution networks (denser = more economical route structures can be created); businesses where learning can be shared (consulting); retailers (larger scale buyers like Walmart can push for better pricing).

More technically, the pricing power of a leader with scale economies lies in "the profit margin the business with power can expect to achieve if pricing is such that its competitor's profits are zero." In other words, the Surplus Leader Margin = [Scale Economy Intensity] * [Scale Advantage].

Chapter 2: Network Economies

You have network economies when "the value of a product to a customer is increased by the use of the product by others." For example, LinkedIn (for both recruiters and users), or Facebook (for both advertisers and users). This allows the leader to charge higher prices and makes it very expensive for a competitor to gain share. Companies with this power often have a decisive early product (with staying power), and the business itself tends to be "winner take all." That said, a limitation is the boundedness of the character of the network: Facebook for personal and LinkedIn for professional interactions.

Be aware of the possibility of the positive network effects with no potential for power (e.g. if there is no underlying monetization model, as with Twitter). And there are some economies with indirect network effects (app stores, where the benefit is demand generation for other players like developers).

Chapter 3: Counter-Positioning

Counter positioning is characterized by a new entrant with a superior and different business model that can successfully challenge formidable incumbents while the latter remain "seemingly paralyzed and unable to respond." E.g. Vanguard (upstart) vs. Fidelity, Dell vs. Compaq, Amazon vs. Borders, Netflix vs. Blockbuster. The benefit side is clear cut: the new business model is superior in some way.

The interesting angle is the barrier side: within the counter-positioning context, the incumbent cannot pursue the new business value without severely damaging their existing business. Note that if the new business model is not attractive to the incumbent as a standalone business, it doesn't count as collateral damage. [Though it does depend on how you define your business, and whether you fall into marketing myopia.] Instead, there are three "rational" reasons, due to counter positioning, why a company might not invest.

Milk the existing business: often beneficial in the short term. However, as the entrant grows your ability to milk is lost while the uncertainty of the new business model's viability is reduced. (This is why delayed entry into the market is a rational response.)

Disbelieve or discount the potential value of the new business: common due to cognitive bias or the "history's slave" cultural trap from the incumbent's earlier success, even if the new model is judged attractive.

Disconnects between what's good for the incumbent business itself and the employees (whose jobs, compensation, etc. might be tied to that current business and eliminated if they switch) also might cause the business not to invest in an attractive new model.

Counter Positioning is different from the concept of Disruptive Technology, though they might be related in some circumstances. For example:

Counter Positioning Only: In-N-Out vs. McDonalds (no new tech involved)

Both CP & DT: Netflix streaming vs. HBO via cable

Disruptive Technology Only: Kodak vs. digital photography (given Kodak's power was from film sales)

It is critical to consider counter positioning "relative to each competitor, actual and implicit." If you believe you have counter positioning power, avoid trumpeting your superiority, as it reinforces the cognitive bias component of the incumbent. Remember: you must take advantage of the strengths of the incumbent and set it up where you can win even if they play their best game. Note that if you work within an incumbent, recognize that "a counter positioning challenge is one of the toughest management challenges" you might ever face.

Chapter 4: Switching Costs

You have switching costs “when a consumer values compatibility across multiple purchases [whether the same or complementary products] from a specific firm over time.” Benefits are being able to charge higher prices for your current customers who are locked-in. Competition is locked-out unless they are so compelling as to pass the hurdle of switching costs for the customer. These are either a) financial; b) procedural (if you have deeply ingrained and critical processes tied up in your product); and c) relational (if customers are part of a community, or there are other emotional bonds tied up with your product).

Having high switching costs grows the lifetime value of customers significantly, and competition for net new customers can become fierce. Note that this power can be enjoyed by all players, though technological developments can eliminate these advantages. Also, having high switching costs can spill over into other powers, like branding (if you have marquee customers locked-in who influence other potential customers) and network effects (with complementary goods).

Chapter 5: Branding

You have branding power when your brand "is an asset that communicates information and evokes positive emotions in the customer, leading to an increased willingness to pay for the product." This is manifested both as good emotional feelings about the product and reduced uncertainty about the product. It takes a long period of continual investment and reinforcement (hysteresis) to create a strong brand, which serves as the barrier. (Don't expect an immediate payoff).

If you have branding power, you will want to protect against: a) brand dilution (from releasing products which deviate from or damage the brand image); b) counterfeiting (from others who want a free ride by associating with you); c) changing consumer preferences (as Nintendo was "family friendly" as gamers aged out); d) geographic boundaries (what is strong in the US is not necessarily the case in other countries). It's also important to consider: e) narrowness (brand power is not the same as brand recognition); f) non-exclusivity (your competition can enjoy this too); g) the type of good involved (there must be the promise of an eventual price premium from your brand, and for a long enough time to matter).

Chapter 6: Cornered Resource

Cornered resources are characterized by a company having "preferential access, at attractive terms, to a coveted asset that can independently enhance value." E.g. a proprietary & patented technology for less expensive manufacturing, or sole access to a specific plot of land (for development), as long as the cost of that resource doesn't cancel out the benefit to the company.

Cornered resources must be "sufficiently potent to drive high-potential, persistent differential margins, with operational excellence spanning the gap between potential and actual." There are five screening tests to isolate the power source. It must be: 1) idiosyncratic (e.g. if a company repeatedly acquires some type of resource at attractive terms, then maybe their discovery process is the actual cornered resource); 2) non-arbitraged (the resource does not cost anywhere close to the true value it creates); 3) transferable (if it only creates this much value within the context of this company, it's not "coveted"); 4) ongoing (the value creation is ongoing, only ceasing if the resource is taken away); and 5) sufficient (the cornered resource alone is sufficient for differential returns, assuming operational excellence). With some exceptions, leadership teams do not usually qualify as a cornered resource because they tend to fail the sufficiency requirement.

Chapter 7: Process Power

You have (rare) process power when "embedded company organization and activity sets enable lower costs and/or superior product, which can be matched only by an extended commitment." E.g. Toyota's production system led to huge benefits (quality of products, cost efficiency of manufacturing, persistence over time) and huge barriers (complexity to replicate and opacity to outsiders despite giving tours of their factory and attempting to explain how it all worked).

Process power is distinct from operational excellence, which is argued (by Michael Porter) as not the same as strategy, since anything which can be mimicked is not strategic. Instead, process power is operational excellence with hysteresis, the long period of continual investment and reinforcement as seen with branding power. Process power is also distinct from experience, which while it may reduce the cost of goods sold as you get better, does not capture the relative power you might have over a competitor at a given moment in time. Process power is reflected in the underlying routines [a.k.a. culture] of a company. [For more on routines, see Richard Nelson's An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change.]

PART II: STRATEGY DYNAMICS

Chapter 8: The Path to Power (a.k.a. How to Create Power)

Creating power requires invention. Operational excellence alone is “table stakes” for a successful business and, while it requires the majority of management’s time, will not be a source of power. Strategy - your route to power - cannot be designed in advance, but must be crafted over time, with breakthrough opportunities recognized and seized along the way. For example, as Netflix moved beyond the DVD business and into streaming (in which they had no power), they successfully navigated various operational challenges (UI, recommendation engine, IT infrastructure) before realizing that content was at the heart of the problem (of creating and building power).

Review the seven types of power and ask, "How do we get there?" (All quoted):

Scale Economies. Simultaneously pursue a business model that promises Scale Economies (industry economics), while at the same time offering up a product differentially attractive enough to pull in customers and gain relative share (competitive position).

Network Economies. Similar to Scale Economies, except that installed base, rather than sales share, is the goal.

Cornered Resource. Secure the rights to a valuable resource on attractive terms. This often comes from having developed that resource in the first place and then gaining ownership of it, the most common avenue being a patent award for research developments. [Or original content developed by Netflix.]

Branding. Over an extensive period of time, make consistent creative choices which foster in the customer’s mind an affinity that goes beyond the product’s objective attributes.

Counter-Positioning. Pioneer a new, superior business model that promises collateral damage for incumbents if mimicked.

Switching Costs. With Switching Costs, first attain a customer base, meaning the same new-product requirements demanded of Scale and Network Economies factor in here as well.

Process Power. Evolve a new complex process which renders itself inimitable within a reasonable period and yet offers significant advantages over a longer period of time.

Invention, the main source of power, is a combination of action, creation, and risk taking, fueled by passion, domain mastery, and monomania. This typically happens when external conditions are in high flux (creating new threats and opportunities), and especially when progress in the market is being made in fits and starts. Focusing on creating compelling value, observed as customers experiencing the “gotta have” response. Note the three guiding paths for creating compelling value based on what is known or unknown in the market:

Capabilities led: Unknown product/market fit. It may take a long time to turn a particular capability into a compelling product if the customer’s needs are unknown. Often this relies on broader market conditions creating windows of opportunity to capitalize on your capabilities (e.g. Adobe Acrobat).

Customer led: Unknown how to meet a known need in the market. For example, the principles (and massive opportunity) behind fiber optics were well known, but not achieved at scale until Corning Glass developed the technology to make it possible.

Competitor led: Unknown whether you will be able to leapfrog an existing, successful competitive product. For example, Sony Playstation anticipated the large opportunity from game consoles moving into 3d graphics, although they had to make large, risky commitments upfront to make it possible (to succeed alongside incumbents Nintendo & Sega).

Chapter 9: The Power Progression (a.k.a. When to Create Power)

Each of the 7 powers can only be established during very specific market / company moments. Achieving power relies heavily on operational excellence, strong leadership, as well as luck, timing, and other factors. For example, Intel's famous leadership team - Noyce, Moore, Grove - successfully created power within microprocessors (through the famous “Operation Crush” and landing the IBM contract at a critical moment in the explosion of PC sales) even while they failed to create meaningful power within the memory business.

Stage 1: Origination, or before the market takes off, during which there are no lasting benefits of leading the pack. During this period you can establish:

Cornered Resources: whether a unique leadership team, or rights to your invention, benefit is created mainly if it exists before the market takes off (when the true return is realized).

Counter-Positioning: any new business model which traps incumbents in the "vexing damned if you do/damned if you don't cul-de-sac" must come before the phase of explosive growth.

Stage 2: Takeoff, or during the period of explosive growth out of which a leader emerges. This happened for Intel during "Operation Crush." During this period, you can establish:

Network Economies: Cumulative market growth brings the tipping point after which new customers, developers, partners, etc. will flow to the clear market leader. E.g. Android vs. iOS.

Scale Economies: Cumulative market growth also brings the tipping point after which the leader begins to benefit from Scale Economies, if relevant.

Switching Costs: if there are high switching costs within the product or market, these start to get locked-in as more and more customers firm up their decisions and the product matures.

Stage 3: Stability, or after the "explosive" growth phase (rule of thumb: when the market growth drops below 30-40% per year), even if the market continues to grow.

Process Power: Since this is distinguished as operational excellence sustained for a long period until the processes are "sufficiently complex or opaque to defy speedy emulation," this can only come after the initial period of explosive growth.

Branding: Since this is similarly distinguished from brand recognition (which may be relevant within the Takeoff phase), Branding power is established over a longer, stable period of maintaining and reinvesting in the brand.

Interestingly, the barriers to challengers (as reflected in the 7 Powers reference chart at the beginning) are each established within specific period of time: Collateral Damage and Fiat barriers come from the Origination stage; Share Gain Cost/Benefit barrier comes from the Takeoff stage; Hysteresis barrier comes from the Stability stage.

Operational excellence (both leadership and execution) is critical within the context of the dynamics of Power. Shipping a poor product during the Takeoff stage can cause you to lose an early lead (e.g. the Apple III). Companies stuck on a treadmill of being a business without Power in a stabilized market (or with its power eroded away) will continue to decline despite efforts of leadership.

[Appendix 9.1 offers an excellent synopsis of the book, with commentary from the author.] In summary, the 7 Powers is intended to be a simple and usable framework, without being simplistic. The overarching goal (the Mantra) is to find the"route to continuing Power in significant markets." The author has found these 7 Powers to be sufficient to analyze the relative success of one company over others in different situations, and the "potential for these Power types is usually evident long before detailed forecasting is possible." Another benefit of this small set, especially organized within the time frames, is to focus operational excellence efforts on those which will establish lasting power.