High Output Management, by Andrew Grove

My full summary of this classic in effective management.

📣 FINAL REMINDER: Coming up on Wednesday, May 31st, I will be cohosting a live book talk on Crucial Conversations withJulia Levy, editor ofThe Switchboard. Come join us!

Andrew Grove packs a LOT of insight into this relatively short book. It’s the kind of book I would re-read on a yearly basis, if I didn’t already have my own summary notes.

One thing I love about reading classics (like this one) is when we enjoy all of the echos of his ideas through many of the other management books from the subsequent 40 years. For example:

Management by Objectives (Chapter 6), which became famous as OKRs (Objectives and Key Results)

The components of effective meetings (Chapter 4), with an emphasis on the one-on-one as a source of managerial leverage.

Hybrid organizations (Chapter 8), where individuals have a balance of functional team and project team membership.

Each chapter is hyper-focused on some important element of management: finding leverage, the value of training, how to keep employees motivated, and more. If you enjoy reading this summary, make sure you take a crack at the whole thing too. You don’t be disappointed. Find it on Amazon or Bookshop.

Introduction

High Output Management was originally written in 1983. In the 1995 introduction, the author recognizes two major trends:

Globalization has taken over business, meaning that “every employee will compete with every person anywhere in the world who is capable of doing the same job.” Also, “When products and services become largely indistinguishable from each other, all there is by the way of competitive advantage is time.”

Email has begun to transform how information flows and is managed, leading “a lot more people know what’s going on in your business than did before, and they know it a lot faster than they used to.”

Increasing competition and speed of disruption requires all managers to develop a high tolerance for disorder. This is especially true for vital “know-how” middle managers who are sources of “knowledge, skills, and understanding to people around them.” Real work is done by teams, not individuals, and their output is all that matters, not their activities.

Useful prompts for a curious manager to ponder: a) Are you adding real value or merely passing information along? b) Are you plugged into what’s happening around you (both in your company and the industry) or do you wait for a supervisor to interpret whatever is happening? c) Are you trying new ideas, new techniques, and new technologies?

PART I - The Breakfast Factory

Chapter 1: The Basics of Production - Delivering a Breakfast

The basic requirement of production is to “build and deliver products in response to the demands of the customer at a scheduled delivery time, at an acceptable quality level, and at the lowest possible cost." [Grove provides an ongoing example of delivering a breakfast of coffee, toast, and a perfect 3 minute egg.] Key concepts:

The limiting step is whatever takes the longest to prepare. [This is likely the 3-minute egg, but if you wait 5 minutes to access the toaster, it becomes the toast.]

Production operations come in three main types: a) process manufacturing (which changes the material); b) assembly (when components are put together in some way); and c) testing (what you have is examined to make sure the customer’s demands are being met).

Throughput can be increased by a) asking for help (increases dependencies, lowers predictability); b) hiring specialists (increases overhead); c) adding capital equipment; or d) building up finished-goods inventory (carries risk of not being sold).

A continuous operation (e.g. a continuous 3-minute egg boiler) can dramatically lower costs, increase throughput, and improve quality … at the expense of flexibility.

Quality is maintained through functional tests (of the actual product itself, which may be destructive) or in-process tests (especially of the equipment, e.g. checking the temperature of the water used to boil the eggs).

Quality is also maintained through incoming or receiving inspection of raw materials. Keep a reasonable (if expensive) raw materials inventory in case you need to reject future deliveries.

Goal: “detect and fix any problem in the production process at the lowest value stage possible."

Chapter 2: Managing the Breakfast Factory

Principles of management come into play when we set indicators, or measurements to monitor and manage output without needing to be physically present. Key indicators for the breakfast factory production line would cover: a) sales forecasts (including the variance prior periods had with their forecasts); b) raw material inventory (to adjust or cancel any deliveries); c) the condition of your equipment (to mitigate downtime and plan future repairs); d) the status of your manpower (did anyone call in sick?); and some kind of quality indicator (are customers enjoying themselves?). Key tips:

Pairing indicators helps to prevent overreacting. E.g. monitoring both inventory levels and the incidence of shortages keeps each in balance.

Effective indicators cover the output (sales orders) of the work unit and not simply the activity involved (sales calls). Aim for physical, countable things paired with a quality indicator to make sure work is not getting sloppy.

Leading indicators give you an advance look at what the future might look like, and are only valuable if you believe in their validity. If you’re not prepared to act on them, they’ll only create anxiety. Visualize indicators in a way that gives you a feeling for what’s happening in your business.

Problem: “CEOs always act on leading indicators of good news, but only act on lagging indicators of bad news."

Build to order minimizes built inventory risk yet creates long lead times (bad for customers and may hurt competitiveness). Build to forecast is better for customers, but creates risk if your forecast is wrong. Ideal is to have the finished product and the customer’s order arrive simultaneously.

It’s generally best for forecasts to be set by the people responsible for hitting them.

Any system will need slack to accommodate unexpected events. It’s generally best to keep inventory in the lowest-value stage possible to maintain production flexibility.

Accepting substandard raw materials is okay as long as it never leads to a complete failure - a reliability problem - for the end user. Maintain quality using in-process monitoring tests; test more frequently where you have less consistent results. Identify and reject defects as early as possible in the production process.

Improve productivity through a) finding higher leverage activities (or increasing the leverage of activities); and b) continuous simplification of work.

PART II - Management is a Team Game

Chapter 3: Managerial Leverage

A manager’s output is the output of their organization + the output of the neighboring organizations under their influence. This means individual contributors with great power within the organization (often due to gathering & disseminating know-how and information) should also be seen as managers.

Managerial activities often fall into categories: information gathering, nudging, decision making, and role-modeling. Spend ~75% of the time on information gathering so you have what you need to make decisions. Quick & casual exchanges are often the most valuable.

People who ask you to do something will often shower you with useful information (regardless of whether you do what they ask).

“Reports are more a medium of self-discipline than a way to communicate information. Writing the report is important; reading it often is not.” (Same for annual planning processes).

The manager must also be a source of information, particularly around "objectives, priorities, and preferences as they bear on the way to approach certain tasks.” This is key to delegation.

An important portion of leadership lies in being a role model for others. Visibly live the values and behavioral norms. “Taking your work seriously” is an important quality to communicate.

Managers have leverage in that the output of others is influenced by their actions, and the art of management lies in identifying the handful of activities (today) that have significantly higher leverage and focusing on them.

High-leverage activities are those where a) when many people are affected; b) when one person is affected for a long period of time by a brief action; or c) when the work of a large group is affected by a key piece of information.

Leverage can be positive (e.g. setting clear guidelines for the planning activities of a large team) or negative (e.g. coming to a meeting unprepared, waffling on a decision, acting depressed, or meddling with subordinates and destroying their autonomy).

When you delegate, make sure you let go. It’s okay to monitor, but monitor the right things. E.g. when you delegate decision making, monitor their decision making process.

Pay close attention to how you allocate your time, day to day, so you can stay focused on the highest leverage activities possible. "Forecasting and planning your time around key events (such as rate-limiting projects or batching common activities like reading emails) are literally like running an efficient factory.”

Don’t just passively collect “orders” for your time. Maintain slack in your schedule, say “no” to things beyond your capacity, maintain a raw material inventory of (unstarted, yet promising) projects, and develop efficient systems for handling recurring activities.

Plan to spend a half-day per week for each subordinate; someone in a sole supervisory role should have nore more than 6-8 direct reports.

Interruptions happen: it’s your job to make sure people have information they need to be successful. Do your best to shepherd interruptions into regular, predictable patterns.

Chapter 4: Meetings - The Medium of Managerial Work

A meeting is a high-leverage medium through which managerial work is performed. It’s important to design meetings carefully so they have positive leverage. Process meetings (which are infused with regularity, with common objectives and structure) commonly include:

One-on-ones: most effective when ~1 hour (to go beyond quick updates). Focus on teaching & exchange of information. Aim to have the subordinate drive the agenda, but guide the conversation to cover potential problems as well. These sessions can exert enormous leverage, particularly if one hour can impact their next 80 hours of work.

Staff Meetings: regular peer-group meetings with the goal of having the subordinates bearing the brunt of working the issues. Supervisor’s role Is as moderator and facilitator, keeping things on track. Aim for “dinner-table conversation of a family” instead of the “group of strangers” you see during ad-hoc meetings (see below).

Operation Reviews: opportunities for cross-functional teams to come together and learn from each other. The senior “reviewing manager” should not preview materials beforehand, and instead act as a role model to provoke audience participation. The supervisor of the presenting managers should manage all other aspects of the meeting, including quality of the discussed materials. Attendance is not a siesta from work, so pay attention and participate.

Mission-oriented meetings (called for an ad-hoc purpose) are risky, and it’s a “sign of malorganisation when people spend more than 25% of their time in ad hoc mission-oriented meetings.” Some tips for navigating these successfully: a) know the objective; b) no more than 8 people; c) maintain discipline and never be late (especially as the chairman); d) provide a detailed agenda stating the roles people are to play (and re-stating the objective); e) take minutes (and send them out soon afterwards).

Chapter 5: Decisions, Decisions

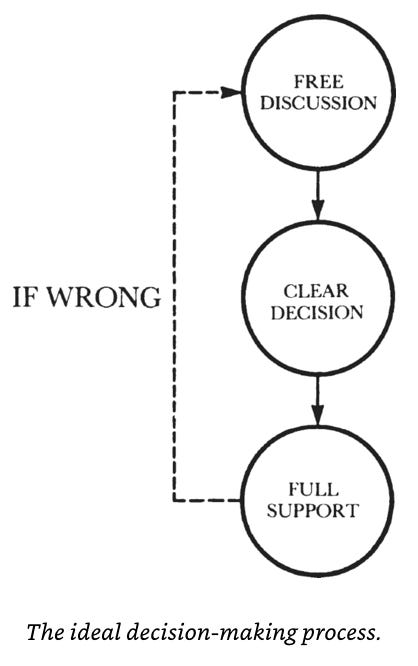

The ideal decision process is simple. It proceeds from a) free discussion (capturing points of view,); to b) a clear decision (well understood by everyone); with c) full support of everyone involved (even if they disagree).

Aim for discussion to connect people with power based on position with people with power based on knowledge.

Common struggles (often experienced by middle managers): a) expressing their views forcefully; b) making unpleasant or difficult decisions; and c) truly supporting decisions where you disagree.

Have people closest to the underlying situation (the lowest competent level) be the ones to work out and reach decisions for their situation

Watch out for Peer-Group Syndrome - when peers dance around the main issues, trying to feel each other out and determine the emergent consensus before articulating their point of view.

Remember: “Nobody has ever died from making a wrong business decision, or taking inappropriate action, or being overruled.” Just try not to do this too early or too late.

Clarify the output of the meeting by asking the following in advance: 1) What decision needs to be made? 2) When does it have to be made? 3) Who will decide? (Hopefully a mix of people with differing perspectives/objectives) 4) Who will need to be consulted? 5) Who will ratify or veto the decision? 6) Who will need to be informed?

“Group decisions do not always come easily. There is a strong temptation for the leading officers to make decisions themselves without the sometimes onerous process of discussion.” [Sloan]

Chapter 6: Planning - Today’s Actions for Tomorrow’s Output

We all engage in planning - taking actions now to affect future events. Any painful gaps between environmental demand and your current status indicates failure of prior planning. There are three main steps, where the true output of planning are decision made and actions taken:

Identify Future Environmental Demand: this is the difference between what customers expect from you now and what they may expect in the future. Ignore limitations; seek to forecast the real demand.

Identify Present Status: this includes present capabilities (including project throughput), projects in the pipeline, and expected completion dates. Will everything be completed?

Identify What To Do To Close The Gap: this includes both what you need and what you can do (and when). The set of actions you decide on is your strategy. Remember: every time you commit to something you implicitly say “no” to something else. Also, what one level considers strategy the level up may consider tactics.

Management by Objectives (now known as OKRs) make steps 2 & 3 very specific. Two prompts: a) where do I want to go? (objective); and b) how will I pace myself to see if I’m getting there? (key results). Some tips:

This should provide focus (through a small set of carefully-selected objectives).

This should provide rapid feedback specific to the objective (so remedial action can be taken).

A manager’s key result could be the objective of their subordinate (they can cascade down)

Someone should be able to fail at their specified objective yet still perform well. [E.g. Columbus failed to find a new trade route to Asia, yet he still unlocked fabulous wealth for Spain.] Resist mechanically using OKRs in performance reviews. Acknowledge emerging opportunities.

PART III: TEAM OF TEAMS

Chapter 7: The Breakfast Factory Goes National

The complexity of management increases as an organization scales across new lines of business or locations. This requires working through tradeoffs of centralization vs. decentralization in purchasing, real-estate, construction, HR, marketing, etc. Management is not just working within your team; it involves creating a team of teams to handle things effectively.

Chapter 8: Hybrid Organizations

A primary challenge of any organization is to strike the appropriate balance between centralization (i.e. with a functional organization of resources, which increases leverage) and decentralization (i.e. with a mission-oriented organization of resources, which improves responsiveness). The most successful organizational structure is some form of hybrid which reflects strengths of both sides. Some tips:

Functional teams are like “internal subcontractors;” they provide help to other parts of the org

Leaning heavily toward functional orientation introduces challenges: a) information overload (too many specific teams to track); and b) unproductive negotiation for relative resources for different competing business purposes.

The only benefit of mission-orientation is that “individual units can stay in touch with the needs of their business or product areas and initiate changes rapidly if those needs change.” This is critical to any business, which is why there is always some sort of mission-orientation.

Even the most distributed teams will have some element of functional leadership & guidance.

“The shift back and forth between the two types of organizations can and should be initiated to match the operational styles and aptitudes of the managers running the individual units.”

Executive management is too far from the individual situations to allocate resources appropriately. This must lie with middle managers closer to the issues.

Chapter 9: Dual Reporting

Dual reporting is the most effective mechanism through which hybrid organizations are managed. This is where the individual middle manager reports directly to their mission-oriented business leader and to their respective functional head. This creates ambiguity for the manager, but it’s necessary for a successful hybrid organization. Being strictly functional means losing the important connection to what your customers want; being strictly mission-oriented means creating inexcusable inefficiencies. Tips:

For example, a security guard would report to both the security manager (who specifies how the job ought to be done) and the plant manager (who is on-site and monitors how it is being performed day-by-day).

Functional management can be done by a peer-group, as long as the peers voluntarily surrender their individual decision making to the group. The trust this requires is engendered by a strong and positive company culture. (Think of the trust required to travel with friends.)

“The need for dual reporting is [not] an excuse for needless busywork, and we should mercilessly slash away unnecessary bureaucratic hindrance, apply work simplification to all we do, and continually subject all established requirements for coordination and consultation to the test of common sense.”

Multi-plane organizations are another way of tackling complexity within organizations. This is where an individual can also be part of another coordinating group with its own organizational chart that does not interfere with “official” roles. Benefits include increasing leverage, dissolving the “official” hierarchies within working groups, and enabling temporary teams to be gathered to address critical issues. Drawbacks are mainly that these roles vie for the time of a given manager, leading to further ambiguity in their priorities.

Chapter 10: Modes of Control

The appropriate mode of control depends on the motivations of the individual (from self-interested to group-interested) and the CUA factor (the degree of complexity, uncertainty, and ambiguity) in the environment. When individuals are group interested, you can lean into contractual obligations (like an employment contract) for the low CUA circumstances, or cultural values for higher CUA situations. When individuals are self-interested, you either have free market forces for low CUA circumstances (like buying tires), or complete chaos and people fleeing a sinking ship with high CUA situations. Other tips:

Management negotiates (and supervises/enforces) contractual obligations, and they cultivate cultural values (shared trust, your company’s methods for navigating complexity, uncertainty, and ambiguity) through articulation and example.

Low level jobs tend to have a relatively low CUA factor. After proving performance, you get promoted into roles with increasing CUA factor.

Senior members hired from outside of the company should aim to quickly reduce their individual CUA factor. Do this by learning the cultural values that pull people together.

Expectations are built over time - e.g. of annual retreats - and can become the equivalent of contractual obligations even without legal documents. (As with anything else that directly appeals to self-interest).

PART IV: THE PLAYERS

Chapter 11: The Sports Analogy

To maximize our output, we must find ways to keep our subordinates in peak performance. This can be done through training (if competence is the issue) or motivation. For the latter, a manager can only affect the environment that influences motivation. Other tips:

If you don’t know whether an issue (with low performance) is due to competence or motivation, ask: Would they be able to do this if their life depended on it?

“A need once satisfied stops being a need and therefore stops being a source of motivation. Simply put, if we are to create and maintain a high degree of motivation, we must keep some needs unsatisfied at all times.”

Grove draws inspiration from Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, where higher ones take over once lower ones are satisfied, starting with physiological & security / safety needs, then …

Social / Affiliation needs: desire to belong to a group. This is a powerful basis for organizational culture.

Esteem / Recognition needs: desire for the esteem of someone you respect. Motivation may lapse when people accomplish their (often imagined) goal.

Self-Actualization Needs: desire to become your best (which has no limit), either defined internally (competence-driven) or externally (achievement-driven). Motivation persists as people continually set their own bar higher, spontaneously testing their own abilities.

When motivated by self-actualization, money is a measure of progress. Fear is a fear of failure.

Sports Analogy: “Imagine how productive our country would become if managers could endow all work with the characteristics of competitive sports.” E.g. where there are clear rules for the game, ways to measure your performance, and recurring opportunities to “go up against someone else” from a blank slate so that failures/losses are turned into opportunities to learn.

A manager should operate as a “coach” where they a) take no personal credit for the success of the team; b) are tough on the team to get the best performance; and c) were a good player at one point themselves and therefore understand the game well.

Chapter 12: Task Relevant Maturity

Adjust your communication style and approach based on the task relevant maturity (the TRM) of the subordinate, which is “the combination of the degree of their achievement/competence orientation and readiness to take responsibility, as well as their education, training, and experience.” As someone grows, “structure moves from externally imposed to being internally given.” Other tips:

The TRM of a person or group will vary depending on the context. Someone might have high TRM in a routine situation, and low TRM in novel situations.

Optimal management styles (delegate, don’t abdicate): a) structured & task-orientated for low TRM; b) individual-oriented communication, support, and mutual reasoning for medium TRM; and c) minimal manager involvement, clear objectives and monitoring for high TRM.

Learning by making mistakes is not okay if customers are the ones paying for their teaching.

Increase leverage by increasing your subordinates’ task-relevant maturity. Just remember to adjust your style of working accordingly to not sabotage their progress and lose effectiveness.

Workplace friendships are great as long as you are okay delivering a tough performance review.

Chapter 13: Performance Appraisal - Manager as Judge and Jury

Performance reviews are the single most important form of task-relevant feedback we can provide. A lot depends on reviews - compensation, promotions, and (most importantly) employee motivation to improve performance - so take the time to do it well. The single most important goal is to improve performance by identifying and addressing skill gaps and nurturing motivation to improve. Tips when assessing performance (and remember, this requires judgment since crystal clear causality is a myth):

Consider both output measures and internal measures. Normalize future-oriented activity based on the “present value” of their work.

Consider the time factor of their performance. Don’t get too caught-up in organizational output/performance stemming from decisions made years ago by other people.

As subordinates or peers: “How did they add value to their team?”

Avoid the “potential trap” where we focus on evaluating potential instead of performance.

Make sure the manager’s review is no higher than how you’d rate the organization as a whole

Delivering an assessment can be a challenge, so use the 3 “L’s”: a) level with your subordinate; listen to them (in all ways, don’t just deliver it in a rote voice); and leave yourself out (this review is about them, and them alone). Make sure to give time for your subordinate to read the review and compose your thoughts before the meeting. There are three types of performance reviews:

Mixed Reviews (“on the one hand, on the other hand…”): Gather all observations, identify common elements, and focus on the most important aspects at a level of detail they can work with. Acknowledge “surprises” if you discover something you were not previously aware of.

Negative Reviews (“the Blast”): Walk them through the stages of problem solving (Ignore -> Deny -> Blame Others -> Assume Responsibility -> Find Solution). Gain their commitment on some solution (which you will then monitor). Moving from blaming others to assuming responsibility is an emotional step, but you can force the issue as their manager.

Script: “This is what I, as your boss, am instructing you to do. I understand that you may not see it my way. You may be right or I may be right. But I am not only empowered, I am required by the organization to give you instructions, and this is what I want you to do…”

Positive Reviews (“the Ace”): Resist the temptation to only pat them on the back for good performance. Take the time to focus on their performance and help them also improve.

Final tips: a) make sure to write your review before reading any self-reviews they may have written themselves (they will feel cheated if you take short-cuts); b) embrace 360 reviews only with an “advisory status” (you and your subordinate are not equals); c) think critically about the reviews you’ve received in the past: analyze them, deconstruct them, and figure out how to do them better.

Chapter 14: Two Difficult Tasks

When interviewing a potential employee, find ways to (concretely) evaluate their performance, either through reference checks or good questions. Ask about subjects on which you both are familiar, whether a) technical knowledge (required for the role); b) how they’ve performed while using their technical knowledge; c) discrepancies between what they’ve known and what they’ve done; and d) operational values that guide them on the job. Tips on interviewing well:

It’s up to you to use the time effectively. If needed, interrupt them.

If possible, follow-up with them after talking with references (to fill in gaps).

Luck is also involved with hiring; do your work in the hope of improving your luck.

When attempting to keep a valued employee who is quitting, drop everything (even that important meeting) and respond appropriately in the exact moment when they tell you. Tips on handling this well:

Get them to talk about why they are quitting. Don’t argue about anything, only seek to learn the underlying reasons. Convey to them through what you do that they are important.

Vigorously pursue every avenue available to keep them at the company, even if it means transferring them to another team. Do what is right for the business.

Script: “You did not blackmail us into doing anything we shouldn’t have done anyway. When you almost quit, you shook us up and made us aware of the error of our ways. We are just doing what we should have done without any of this happening.”

Script: “You’ve made two commitments: first to a potential employer you only vaguely know, and second to us, your current employer.”

Chapter 15: Compensation as Task-Relevant Feedback

Most people will be motivated by the relative amount of a raise, so make sure this is calibrated to deliver task-relevant feedback. Other notes:

Base bonuses on a balance between a) countable items (financial performance), b) achieving measurable objectives, and c) subjective elements (which might be a kind of beauty contest).

Avoid creating a bonus model that contractually obliges you to pay people lavishly if the company is going bankrupt.

Basing pay raises on experience-only communicates you don’t care about performance. Basing pay raises on merit-only fails to create fair salaries in the broader market. Strike a blend of both where the steepness of the pay increase curve goes up with performance, and promotions mean shifting up to the next salary progression curve (where someone who exceeded expectations in their prior role can now “meet expectations” in the current role).

Chapter 16: Why Training Is the Boss’s Job

Training is one of the highest leverage activities a manager can perform. This is not something that can be outsourced. For it to be effective, it must a) maintain a reliable, consistent presence (not as a rescue effort to solve the problem of the day); b) be closely tied to what you practice in your particular organization / team; and c) must be done by the appropriate role model, a.k.a. you. Other notes:

There can be serious consequences when employees are insufficiently trained.

Take the training schedule seriously. Work with others who can help you find leverage in it.

Tackle the challenge of course creation iteratively. Design a 3-4 lecture series, write the first lecture, and just go. Write the second lecture after you give the first, so you can adjust it accordingly. And improve it/ train other trainers through the various iterations.

Becoming good at training others is exhilarating. It helps you solidify your own knowledge of the material.

One More Thing

[Grove provides a helpful set of exercises to implement the concepts of the book and improve your own performance as a manager.]

Great summary! Which other books do you recommend product leaders re-reading annually besides High Output Management?