Build, by Tony Fadell

My chapter-by-chapter notes on his indispensable advice on building a successful and meaningful career, product, and business.

This is the longest summary I’ve ever written, and for good reason: Fadell has a LOT of wisdom to share worthy of your attention. It’s especially relevant for anyone looking to start their own company, but I find it equally relevant reading this as a product manager seeking ways to deliver excellent products more effectively.

If you’re on the fence at all about buying this book, I’ll offer two reasons. First, his writing style is really compelling and entertaining, and it’s peppered with numerous anecdotes about his experience working at Apple and at Nest. Second, Fadell is pouring all of his earnings from the book into a Climate Fund managed by Build Collective, his investment and advisory firm. So every dollar will go toward saving our planet in some way or another. Here’s a link to buy the book on Bookshop or Amazon.

I hope you enjoy the summary below!

Introduction

"The world is full of mediocre, middle-of-the-road companies creating mediocre, middle-of-the-road crap, but I’ve spent my entire life chasing after the products and people that strive for excellence [and] I’ve been incredibly lucky to learn from the best." [Fadell gives a brief account of his career and positions this book as a way to help anyone seeking to "reach their potential, to disrupt what needs disrupting, to forge their own unorthodox path."

PART I: BUILD YOURSELF

Advice for anyone starting their career or shifting into something new.

Chapter 1.1: Adulthood

Be resolute about following what you're naturally interested in; take risks when choosing where to work. Focus on what you want to learn. Expect to “screw up continually until you learn how to screw up a little bit less."

“The only failure in your twenties is inaction. The rest is trial and error.” Take risks while you have the freedom to make decisions [entirely] on your own.

Stay focused on something “big and hard and important to you” where every step or stumble you take is at least in the right direction.

Don’t kill yourself for your job, but you will need to put in the time to prove yourself and accelerate your learning. “Let your passion for what you’re building drive you."

When you’re young, look for somewhere you can a) realize you have no idea what you’re doing; b) learn from people who can make something great; and c) work hard and have that make an impact.

"Assume that for much of your twenties your choices will not work out and the companies you join or start will likely fail. Early adulthood is about watching your dreams go up in flames and learning as much as you can from the ashes. Do, fail, learn. The rest will follow."

Chapter 1.2: Get a Job

Don't chase blindly after hot trends, cool technology, great teams, lots of funding. Instead, look for a company poised to make a substantial change in the status quo. Criteria: a) they are creating a product or service new enough competition can’t make or even understand it; b) the product solves a real problem that a meaningfully large number of customers experience daily; c) the novel technology is feasible to build into a business (incl. the infrastructure, platforms, and systems that support it the product); d) leadership is not dogmatic and about what the solution looks like and is willing to adapt to their customers’ needs; and e) they are “thinking about a problem or a customer need in a way you’ve never heard before, but which makes perfect sense once you hear it." Some tips:

"Take whatever job you can at one of those companies. Don’t worry too much about the title—focus on the work. If you get a foot in the door at a growing company, you’ll find opportunities to grow, too."

Avoid consulting: you never get the 3-dimensional experience of working in the industry.

Find any degree of community of like-minded people passionate about the problem space you’re interested in. Stay focused on your goal.

Chapter 1.3: Heroes

Find a way to work with your heroes, the best of the best who will lead you to the career you want. [Story of how this brought Fadell to General Magic.] Some tips:

Be persistent, learn as much as you can about your industry, find ways to be helpful or offer something (which you can always do if you’re curious and engaged).

Bill Gurley quote: “I can’t make you the smartest or the brightest, but it’s doable to be the most knowledgeable. It’s possible to gather more information than somebody else.”

Make connections to the people who matter; that is the true key to finding the opportunities you really want.

Working with heroes is hard to do within really large companies (like Google or Apple), where there are layers of organization.

"There is nothing in the world that feels better than helping your hero in a meaningful way and earning their trust—watching them realize you know what you’re talking about, that you can be relied on, that you’re someone to remember. And then seeing how that respect evolves as you move on to the next job, and the next."

Chapter 1.4: Don't (Only) Look Down

Early on, it is important to be heads-down to develop your craft and deliver results as an individual contributor (IC). However, remember to occasionally: a) look up (to management, the overall company mission and strategy, etc. to make sure what you are doing is aligned); and b) look around (to other functional teams to understand their perspectives, needs, and concerns). Some tips:

People have different time horizons: a) CEO & Exec Team focus on the horizon and making sure teams are going in the same direction; b) managers focus on 2-6 weeks out & delivering on the next big milestone; c) junior ICs focus on "getting their specific piece of each project done, done well, and out the door."

Exec team & managers don't always see roadblocks; ICs need to provide that help. "The sooner you start (looking around) the faster and higher you’ll advance in your career."

Seek out (and assimilate) new perspectives, whether from internal or external customers. Listen with genuine curiosity to understand first. Identify the "hard things, brick-wall-like things that emerge from the haze."

PART II: BUILD YOUR CAREER

Advice on how to level up in the most important domains of your career. (Don't be daunted about messing up, everyone does.)

Chapter 2.1: Just Managing

When you're great at what you do (as an individual contributor), chances are you'll get opportunities to stop doing what made you successful and instead help others do the work. Keep in mind:

You don't have to be a manager to be successful. (Star ICs are valuable; pay them accordingly).

As a manager, you’ll need to let go of your desire to do the work. Help others be great.

Skilled management is a learned skill. Seek ways to gather feedback and improve.

Being exacting and expecting great work is not micromanagement. Focus on the output and make sure it's high quality, though don't resort to telling them, step-by-step, how to get there.

Find ways to "respectfully tell the team uncomfortable, hard truths that need to be said"

Your goal should be to have your team outshine you. It lifts you up.

Much of being a good manager relies on knowing yourself and learning how to manage your own fears and anxieties. Invest in your own personal and professional improvement and seek strategies for becoming more effective, but don’t change who you are. Other tips on finding success:

Structure meetings to get you and the team as much clarity as possible.

Learn to modulate your emotions: your team will amplify the mood you bring to work.

The best way to motivate others is to share why you are passionate, why the mission is meaningful, and why the details matter.

Remember that whatever job you hire someone to do is no longer your job. Their success in the role will reflect on you having built a great team.

"It's your responsibility to help (direct reports) work through failure and find success," and then cheer them on when they do well and get promoted.

Chapter 2.2: Data Versus Opinion

When making a business decision, clarify whether it should be a) data driven, where acquiring facts will lend confidence in the choice; or b) opinion driven, where even if informed by data you will ultimately need to "follow your gut and your vision for what you want to do." Some tips:

Data for opinion-driven decisions will always be inconclusive. Avoid “death by overthinking.”

Avoid the two extremes: a) only deciding based on opinion (delusional); or b) only deciding based on data (derivative, or customers dictating the product roadmap).

When people disagree, don’t be afraid to make the call. But you still need to explain yourself. (It isn’t a democracy, but it also isn’t a dictatorship.)

Find a leader who understands the kinds of decisions you’re making and is willing to trust you and back you up. (These kinds of leaders are rare.)

Fear of making the wrong decision, not the decisions themselves, is what kills your product. The most important thing is to keep moving. Act in a timely fashion where you still have time to learn and try something different.

Tell a good story (see chapter 3.2) to get support for a leap-of-faith decision. A good story "convinces leadership that your gut is trustworthy, that you’ve found all the data that could be gleaned, that you have a track record of good decisions, that you grasp the decision makers’ fears and are mitigating those risks, that you truly understand your customers and their needs and—most importantly—that what you’re proposing will have a positive impact on the business."

Common motivations why poor leaders may choose to sit on your idea and ask for more data: a) not wanting to back a risky new project before a promotion or bonus; b) fear for their job if the project fails; c) not seeing the idea as important; or d) not wanting to hurt anyone’s feelings.

"When you’re making something new, there’s no way to definitively prove that people will like it. You just have to ship it—put it out into the world (or at least in front of forgiving customers or internal users) and see what happens.”

Chapter 2.3: Assholes

Someone's underlying motivations and actions are what will help you distinguish between assholes (people you cannot trust, whether selfish, deceitful, or cruel) and people who are simply difficult to work with. Assholes can either be a) overtly aggressive (easy to spot); or b) passive aggressive (more dangerous: they go behind your back to screw you over). When you learn someone is an asshole, don’t directly engage, just rearrange your understanding of the world. Archetypes of assholes include:

Political assholes, who build coalitions and do nothing but take credit for everyone else's work. Strategy: create a counternarrative (which actually serves the customers) to refute the idea-killing BS of these coalitions.

Controlling assholes, who "systematically strangle the creativity and joy out of their team." Strategies: 1) kill 'em with kindness; 2) ignore them; 3) go around them; 4) quit.

Baseline jerks, who deflect feedback as long as they can until others catch on and get rid of them. (Don’t worry about them too much).

In contrast, the mission-driven "asshole" is someone who is not actually an asshole but instead is passionate, ignores office politics, and "steamrolls right over the delicate social order of 'how things are done around here.'" To identify this type of person, ask them “why.” A passionate person will accept the need to explain their decision so you can see it through their eyes. "A mission driven asshole might tear apart your work, but they won't attack you personally."

Chapter 2.4: I Quit

Perseverance is an important trait, yet here's how you know you should quit: a) you're no longer passionate about the mission; or b) you've tried everything but the manager / company / project is falling apart and letting you down. When you do quit, make sure to follow through on your commitments first so you don’t leave anyone hanging. Some tips:

"Hating your job is never worth the money." Avoid talking yourself out of quitting.

Make sure to cultivate relationships with people outside of your work bubble; that's where the best opportunities will come from.

"People won't remember how you started. They'll remember how you left."

When something's not working, don't just complain. Instead, raise issues and bring solutions to people all the way up to even board members and investors. "You'll probably quit anyway if these issues aren't solved, so you have nothing to lose." Changing things will take time.

Make sure issues you raise are about supporting the mission, and not about you.

Quitting should never be a negotiation tactic. It’s "the very last card you play." Make sure you are honest (with yourself) about what you're leaving, and know the story you’ll tell others.

How to avoid getting trapped by your work bubble: "You should talk to people and make connections because you’re naturally curious. You want to know how other teams at your company work and what people do. You want to talk to your competitors because you’re all working to solve the same problems and they’re taking a different approach. You want your projects to be successful, so you don’t just talk to your immediate teammates at lunch—you grab lunch with your partners, your customers, their customers, their partners. You talk to everyone: get their ideas and their perspectives. In doing so you may be able to help someone or make a friend or strike up an interesting conversation."

PART III: BUILD YOUR PRODUCT

Advice on how to build something that people actually want, even if it doesn’t “feel like success at first. Or even in the end.”

Chapter 3.1: Make the Intangible Tangible

Look beyond the specifics of your product and consider all aspects of the customer journey. [With Nest, pivotal moments included a) seeing the product box in the store; b) searching for the right screwdriver to do the installation; and c) spending 80% of their time in the app after the thermostat faded into the background. Also, see image.] Some tips:

Key questions when considering any product: a) "How can you solve your problem without this?" and b) "What is different about the customer journey?" (not what is special about this product)

Expect the customer to ask “why” at each bump in the journey: "Why should I ... care? buy it? use it? stick with it? buy the next version?”

[At Nest, iterating through the tangible packaging drove much of the creative: product name, tagline, priority features, main value props, colors, etc. At Apple, they carried around prototype products in their pockets and built full prototype Apple stores in airplane hangers.]

Turn your early research into two people - distinctive personas with names, faces, and details - you can get to know. (You can add more later on as you better understand your customers.)

Understanding details of your customer’s experience will reveal ways to delight them. [Example of the Nest screwdriver, which was useful far beyond making installation easier, which built brand loyalty.]

Chapter 3.2: Why Storytelling

Good products have stories that: a) appeal to people's rational and emotional sides; b) make complicated concepts simple; and c) focus on why it is truly needed (e.g. the compelling problem being solved). "You can't just hit customers on the head with the 'what' before you tell them the 'why.'" [Example of how Steve Jobs would spend months tweaking each product story with anyone he could tell it to.] Tips on crafting amazing stories:

Prepare people for your solution with the virus of doubt. "Remind them about a daily frustration, and get them annoyed about it over and over again."

"Your product’s story is its design, its features, images and videos, quotes from customers, tips from reviewers, conversations with support agents. It’s the sum of what people see and feel about this thing that you’ve created."

The company that tells the better story will appear to be the leader in the industry.

Find a balance between a) offering information or insights (go too far and people might agree with you but decide it's not compelling enough to buy now); and b) appealing to emotions (go too far and people may see it as truly novel, but not necessary or or too insubstantial.)

Find the analogies that will help your customer grasp otherwise complex and compelling new features (and easily share them with others). [iPod: "1,000 songs in your pocket." Nest's "Rush Hour Rewards" for saving money on days when energy costs were highest.]

"You should always be striving to tell a story so good that it stops being yours—so your customer learns it, loves it, internalizes it, owns it. And tells it to everyone they know."

Chapter 3.3: Evolution Versus Disruption Versus Execution

New products must be something fundamentally new that changes the status quo (disruptive), but not so disruptive you can't deliver on what you promise (execute). Once you have the V1 product, you will need to make incremental improvements (evolve) quickly to stay ahead of your competition, though with an eye toward disrupting yourself. Remember, it's hard to "come up with a great idea and execute it in a way that connects with customers." Some tips:

Truly disruptive products will create enemies; some will love it, some will hate it. Be ready. “You have to choose your battles. Just make sure you have battles."

If your entrenched competitor sues you, you’ve officially arrived. Treat it as good news.

Failure modes for attempts at disruption: a) focusing too heavily on the disruptive element and forgetting it needs to be part of a single, fluid experience; b) setting the truly disruptive part aside because it's too difficult or expensive (which leads to a V1 that is not differentiated); or c) straying too far outside of people's mental models (changing too many things too quickly) where they can't recognize what you've done (e.g. Google Glass).

When iterating, make sure to keep "the quintessential things that define your product" even while everything else changes. (E.g. for the iPod, this was the click wheel).

Underpromise and overdeliver (e.g. with the iPod battery life, they'd relentlessly claw back a few minutes here and there so it would reliably go beyond their advertised duration).

Seek ways to disrupt yourself. "With any disruption, the competition only wallows in Denial and Anger for so long. Eventually they reach Acceptance, and if they’ve got any life left in them, they’ll start working furiously to catch up to you. Or you may inspire a whole new wave of companies who can use your initial disruption as a stepping-stone to leapfrog you."

Success may depend on disrupting parts of the customer journey you didn't anticipate (e.g. distribution channels: Nest partnered with Best Buy to introduce a Connected Home aisle).

Chapter 3.4: Your First Adventure -- and Your Second

V1 product launch: decisions are driven by vision, then customer insights, and lastly data (since data is limited or nonexistent). Your team will mostly be new people, figuring out how to work together. You need to stick to your vision despite internal skepticism [story of Steve Jobs battling for the touchscreen for the iPhone despite Blackberry’s dominance]. If your vision for V1 fails, just learn from the experience, get back to the drawing board, and (eventually) your vision will improve. Key tactic: write a press release when you start working on this version; it helps maintain focus on what truly matters for the customer and can be a litmus test for when the V1 is ready to ship.

V2 product launch: decisions are driven by data (since you can see how customers are using the product, then customer insights, and lastly vision. Your team will hopefully keep much of the same V1 team together while you build out or upgrade the team and become more ambitious. You may need to modify your vision based on what you learn [story of the iPod, originally created to spur new Mac sales, but later was built to work on PCs which unblocked growth.]

Chapter 3.5: Heartbeats and Handcuffs

The best (and most useful) constraint is time, so use deadlines strategically to ensure you make progress. The goal is to create heartbeats that drive the project forward and create predictability for your team and for your customers. These can be either external deadlines (like holiday seasons, or a conference), or strong internal deadlines (for both teams and projects). Some tips:

Set useful constraints across time, money, and even people on the team. "People do stupid things when they have a giant budget—they overdesign, they overthink."

[With the iPhone, the first concept took 10 weeks, the second took 5 months, and only then did they start over and scale up for a third version, which was the V1 they shipped to the market.]

Any truly new project (hardware or software) should ship within 9-18 months, max 24.

"Organize your time into bigger chunks (weeks, months) and take a macro view of your projects." Avoid setting schedules by planning every task in advance; the plan is always wrong.

Involve other teams (sales, marketing, support) within internal project heartbeats to keep everyone on the same page. "These milestones slow you down in the short term, but ultimately speed up all of product development. And they make for a better product."

However fast you move, give customers the time they need to learn how the product works (before you change everything and it's suddenly new again). Don't subject them to thrash.

After launching V1, aim to be announcing a substantial improvement 2-4 times per year.

Chapter 3.6: Three Generations

Expect at least 3 generations of a product (even under the best of scenarios) before you "get it right and turn a profit." It takes time for you (and your customers) to learn. [Fadell maps these idealized generations to the customer adoption curve from Moore's Crossing the Chasm]. "Reaching profitability will take longer than you think."

V1: Not remotely profitable; you've essentially shipped your prototype, so this is for innovators and early adopters who will be okay with a buggy experience. Stay small and be okay outsourcing certain functions. Focus on finding product/market fit.

V2: You're making gross profit on each incremental sale, though you're not yet turning a profit. The most glaring V1 issues have been worked out, enabling you to cross the "chasm" and start reaching the early majority. You begin to bring key functions in-house, and are starting to focus on COGS (cost of goods sold) and CAC (customer acquisition cost).

V3: You’re making net profits on each incremental sale, as revenue starts to outstrip business costs. You’ve built a mature, predictable product that is starting to reach the late majority. You lock-in internal expertise, though you may still outsource non-strategic functions.

Many internet companies took 5-10+ generations of the product before they figured out how to make money (like Google, with Adwords). It is dangerous to take a "swift dive across the chasm" and then spend a lot of VC money looking for a working business model. Stay wary about spending, disciplined about unit economics, and focused on the few differentiating elements of your product. More tips:

"Crossing the chasm isn’t a guarantee, even with much-loved products. And actually making money is much, much harder."

Kickstarter projects usually fail because they only factor in COGS into the price .... "That’s not how companies work. That $150 profit gets sucked away with every new office chair and dependent on your employees’ insurance, with every customer support call and Instagram ad. Until you optimize the business, not just the product, you can never build something lasting."

This evolution happens for every new product you launch. "You make the product. You fix the product. You build the business. Every product. Every company. Every time."

PART IV: BUILD YOUR BUSINESS

Advice on starting & building a business (and staying focused on the big problems to solve).

Chapter 4.1: How to Spot a Great Idea

Three criteria for a truly great idea (for you to work on): 1) it has a clear "why" (see chapter 3.2); 2) it solves a problem a lot of people have in their lives; and 3) you can't stop thinking about it even after extensive research and uncovering all of the challenges. [The Nest Thermostat idea pursued Fadell for 10 years before founding Nest.] Some tips:

Commit to researching & trying your idea before you commit to starting a company.

Aim for painkillers (which you quickly notice if missing) instead of vitamins (not essential).

Make sure the "why" is crisp, persuasive, and easy to articulate.

Find the idea(s) that chase you over time and continually engage your curiosity.

Mapping out the known obstacles will either discourage you (good!) or prepare you for what’s ahead (also good!). Every major bullet you deflect in advance will make you even stronger.

Turn the risks to your business into a rallying cry for your team: embrace them.

Chapter 4.2: Are You Ready?

You're never really "ready" for your first startup. However, you’ll want a mixture of experiences and people you can lean on when you do so you don’t spend valuable time seeking out perspectives on every decision you need to make. Money burns fast. A checklist:

Work at a startup … to have "a working knowledge of each discipline [legal, marketing, sales, etc.]—not to be an expert in each, but to understand who you should hire, what their qualifications should be, where to find them, and when you’ll need them."

Work at a big company … to understand challenges big organizations face beyond the product (processes, governance, politics). (Be careful: only working here won’t prepare you for a startup)

Find a mentor ... to help you navigate everything. Make sure to be coachable (be willing to admit when you screw up). "Find an operational, smart, useful mentor who has done it before, who likes you and wants to help." (Not a business coach who is charging you by the hour.)

Find a cofounder ... to "balance you out and share the load." There can be only one CEO, but you’ll be grateful to have someone you can call at 2am to not be crushed by the weight of it all.

Convince others to join you … especially "seed crystals - great people who bring in more great people" and can almost single-handedly build large parts of your org. Always know the first 5 people you will actually hire when you start. Make sure they’re proven great at what they do, and with the right mindset to navigate a startup.

Make sure you’ve learned from past experiences for patterns you wish to emulate and anti-patterns you want to avoid. Also note that running a startup inside a larger corporation is often just as challenging, so only do this "if [the corporation] can offer you something unique -- some technology, some resources you can't get access to anywhere else." And make sure senior management is ready to provide air cover.

Chapter 4.3: Marrying for Money

Treat every investor relationship as a marriage: take the time to find someone you trust, where you are compatible, they don't play games, your expectations are aligned, and where you understand each other and their priorities. Investors need to be able to convince their LPs they've made excellent investments, so expect to go through a lot of uncomfortable scrutiny. Just make sure you are only raising money when you anticipate actually needing money. Some tips:

Clarify priorities: a VC may “push you to sell or go public before you’re ready in order to show value to the LPs,” and a company VC arm may “may use their investment in your company to wrangle a better business deal for themselves at your expense."

Expect the investment environment to shift between founder-friendly (when investors fund just about anything) and investor-friendly (where terms are worse and investors are pickier).

Know what exactly you'll use the money for. Do you actually need outside money?

Expect a funding round to take 3-5 months. Always plan ahead and nurture relationships.

Always start with a friendly VC who will give feedback now and still invite you back later.

The fund doesn’t matter; it’s ultimately the partner you work with whom you’re marrying. Find someone who a) won't ghost when things get hard; b) won't screw you over to get better terms.

Red flags: a) playing games while "courting" you; b) not helping other companies they've funded (do your due diligence); c) pressuring you to sign too quickly; d) trying to take more than the typical 18-22%; e) trying to screw over other investors with their terms.

Aim for 2 well-regarded partners from different firms on your board to keep each other in check

Always have warm intros, a compelling story, something (PR, press, etc.) to find when they look you up, glowing customer references, and founders with skin in the game (not "fully vested")

Be wary of taking early stage money from family and friends. It brings a high emotional burden.

Chapter 4.4: You Can Only Have One Customer

No matter your business model, only build for one single customer type. [Story of how Apple failed miserably while selling to businesses, but ultimately succeeded in B2B sales by offering compelling consumer products.] "For the vast majority of businesses, losing sight of the main customer you're building for is the beginning of the end." Some tips:

For example, with B2B2C, the businesses who use your products matter, but without the consumer experiencing your product at the end, you have nothing.

This is a challenge with companies who evolve from B2C into B2B2C (like Facebook, Twitter, Google, etc.). "When attention and focus shift away from the consumer and toward the businesses bringing in the real money, companies go down some very dark alleys. And it’s always the consumers who suffer."

Chapter 4.5: Killing Yourself for Work

Perfect work/life balance (where work doesn't intrude on your personal time) doesn't exist when you're starting something new or working on something really ambitious. Create systems of organization to help you prioritize the things which matter, which needs to include taking care of yourself and your relationships. Some tips:

Anti-pattern: Steve Jobs would spend vacations thinking more broadly about Apple, its products, and experiences. Apple was all-consuming.

Build whatever system you need to keep all of the moving parts organized and on-track.

Give yourself periodic breaks, where you do whatever helps you actually clear your head.

Engineer your calendar: create time to breathe, time to reflect, time to have focused and productive sessions, time to make sure you don't push yourself to the brink of collapse.

Recommendations: a) give yourself time (during your workday) to think and reflect 2-3x per week; b) exercise 4-6x per week; and c) eat well so you don't feel like garbage.

If you're reasonably senior, hire an assistant to take on the low-leverage activities (scheduling meetings, etc.) so you can focus on the things which will truly help your team. (Their time is valuable; use it well.)

Fadell developed his own system of organization to meet the grueling (self-imposed) deadlines for the first iPod launch), allowing him to keep everyone fully accountable to what they needed to deliver. “Continually reprioritizing allowed me to zoom out and see what could be combined or eliminated. It let me spot moments when we were trying to do too much.” Notes would be hand-written during meetings to avoid distraction. His system (which may not work for everyone):

Print out the top milestones for all disciplines and most important things needed to be done to reach those milestones.

During meetings, write down promises made (to deliver something by a specific date) along with interesting ideas that needed to be tabled.

On Sunday night, “go through the notes, reassess and reprioritize all tasks, rifle through the good ideas, then [...] print out a new version for the week."

Email the list to your management team and then meet about it on Monday morning.

Chapter 4.6: Crisis

Rules for handling a crisis: a) focus first on fixing the problem, not blaming others; b) get into the weeds (then let people work once they know what needs to happen); c) get advice from others; d) engage in constant communication (talking and listening with everyone who needs to be heard or know what's going on); and e) accept responsibility and apologize for how it has affected customers. Some tips:

People still have limits, even during a crisis. Set expectations on when they'll have a break.

Collect any and all necessary information to be able to answer questions that might come up. You need to be able to instill confidence.

Give yourself full permission to focus solely on the crisis at hand. No nonessential meetings.

Mantra for your team: "We’ll get through this. We’ve done it before. Here’s the plan."

Embed the stories of how you successfully navigated crisis moments into the DNA of your company culture. Celebrate them (after you've survived and learned from them).

"It’s your responsibility as a leader not to try to deal with a disaster on your own. Don’t lock yourself in a room, alone, frantically trying to fix it. Don’t hide. Don’t disappear."

PART V: BUILD YOUR TEAM

Advice on how to develop & hire the people who will build your company, as you proceed through stages of growth. [Nest’s mantra: "We were going to show our investors that this was a world-class team who could perform miracles on a shoestring."]

Chapter 5.1: Hiring

Hiring, onboarding, and developing your people should be the first topic of business in every leadership team meeting. This means: a) maintaining a pipeline of new and experienced talent; b) involving cross-functional perspectives in a defined hiring process; c) and a measured approach to growth and onboarding to ensure you don't dilute your culture over time. It also means firing people who don't work out. Some tips:

Build diverse perspectives into your team. This means a) a mix of really experienced people and promising young talent; and b) people from different backgrounds, perspectives, and experience. This deepens your understanding of your customers and uncovers blindspots.

Vet any candidates with the internal customers they'll need to deliver to. [Nest’s “Three Crowns” approach required agreement between a) the hiring manager; and b) 2 managers of the candidate's internal customers to agree on each hire.]

Use “positive micromanagement” during the first 1-2 months of tenure to help each new hire integrate, understand your expectations, and learn the culture & processes of the company.

Good practice: new hire lunches with the CEO (invite all employees to join a few per year)

Your job as a manager is "to help people identify their challenge areas and give them space and coaching to get better." But if they can't rise to the challenge, you must fire or reassign them.

Sometimes the “people you don’t expect to be amazing turn out to completely rock your world. They hold your team together by being dependable and flexible and great mentors and teammates.” Don’t just wait for A+ hires for every role.

When interviewing, the most important thing is to learn who they are, what they’ve done, and why they did it. Fadell’s favorite interview questions or techniques:

“What are you curious about? What do you want to learn?”

“Why did you leave your last job?” → look for a clear story, try to learn what they did to work through any frustration before leaving, and see whether they left on a good note.

"And why do they want to join this company?” → look for a new and compelling story.

Or, “instead of asking them how they work [...] pick a problem and try to solve it together. Choose a subject that both of you are familiar with but neither is an expert in.” Observe how they think, what questions they ask, and how they frame things.

Chapter 5.2: Breakpoints

You must adapt the organizational design and communication style of your company as you grow, otherwise growth will break your company. "Breakpoints almost always come when you need to add new layers of management, inevitably leading to communication problems, confusion, and slowdowns." To navigate this: a) anticipate & create the new management layers you need (ideally promoting from within); b) communicate the new plan; and c) mentor people as they shift into new roles. Breakpoints typically happen when shifting between teams of the following sizes:

Up to ~15 people: the org chart doesn't matter because it's so flat. Information flows freely. Starts to break when one person is managing more than 8-12 people.

From ~15 ~50 people: one layer exists between the CEO and the rest of the team. Keep the org flat "by avoiding situations where managers only have 2-3 direct reports long-term." Be vigilant for silos starting to form, figure out how to take notes, send updates, and distribute information.

From ~50 to ~140 people: two layers now exist between the CEO and those doing the day-to-day work. Invest in training your managers well: they are primary levers for maintaining communication and alignment (which builds trust). The explosion of people issues requires a real HR team; specialization of ICs is increasingly important; and communication becomes more formalized.

From ~140 to ~400 people: the new challenge is now multiple projects competing for the same resources. Also, "meetings are probably getting out of control and information is getting bottlenecked." Give people ways to connect with each other.

Start preparing for each breakpoint minimum 2-3 months before, and anticipate months of follow-up after. "Think through your org design, your communication styles, figure out if you’ll need to train individual contributors to become managers or bring in new blood, adjust your meetings, see if people scale or not. And you’ll have to talk to people. A lot." Some tips:

Communication must be re-designed with each management layer you add. The key is making sure the same information you communicate to the team is then shared to their teams, and also to “make sure information from throughout the org funnels to the top." Failure breeds distrust.

Avoid the "if it ain't broke, don't fix it" mentality. Expect your org to break and plan against it relentlessly.

People fear specialization when it feels like something is being taken away. "Help them get curious about what their job could become." Focus on what they love and find ways to retain aspects they like. (The same happens with teams needing to focus.)

Strong individual contributors can either a) stay an IC and become layered under someone else; or b) do a management trial (where you ease them into the responsibilities of a manager and really set them up for success).

A manager becoming a manager of managers needs to “think more like a CEO than an individual contributor." Get them adequate coaching, training, and support.

Work to preserve the aspects of your culture that people value most. Sometimes it's the silly things. [At Nest, this was the periodic barbeques as a chance for everyone to hang out.]

"Always remember that change is growth and growth is opportunity. Your company is an organism; its cells need to divide to multiply, they need to differentiate to become something new. Don’t worry about what you’re going to lose—think about what you’re going to become."

Chapter 5.3: Design for Everyone

Cultivate a "design thinking" mindset in everyone. At the most fundamental level, this means a) deeply understanding the problem you're trying to solve; and b) avoiding habituation (e.g. "staying awake to the many things in your work and life that can be better"). Some tips:

Don't fall for the mindset that you just need to hire a good designer to do the hard work of thinking about problems. "You shouldn’t outsource a problem before you try to solve it yourself, especially if solving that problem is core to the future of your business. If it’s a critical function, your team needs to build the muscle to understand the process and do it themselves."

Encourage everyone to challenge the human tendency toward habituation. Seek to continually make things better, for yourselves and your customers. Ask why at every step.

Often the biggest challenge is continuing to notice the problem(s) in the first place. To most people, problems fade into the invisible background (thanks to habituation).

Story: Apple slowed down manufacturing by having the iPod factory tested for 2 hours; this had the (magical & intended) benefit of charging the device fully prior to shipping to be ready for the customer from the first moment.

Chapter 5.4: A Method to the Marketing

The best marketing programs are rigorous and data informed while also rooted in empathy and human connection. Marketing must be involved from the beginning (and is a great way to prototype the product narrative). Ultimately all aspects of the journey are interconnected and must be crafted with care. "The best marketing is just telling the truth (about your product)." Some tips:

Build your messaging architecture (see example) where you cover a) why I want it; and b) why I need it. The need section is split into i) what's my pain; and ii) pain killer. This must describe the whole product narrative and stay as a living, shared document.

Know the most common objections and exactly how you will overcome them (in a way that respects the customer and acknowledges their context).

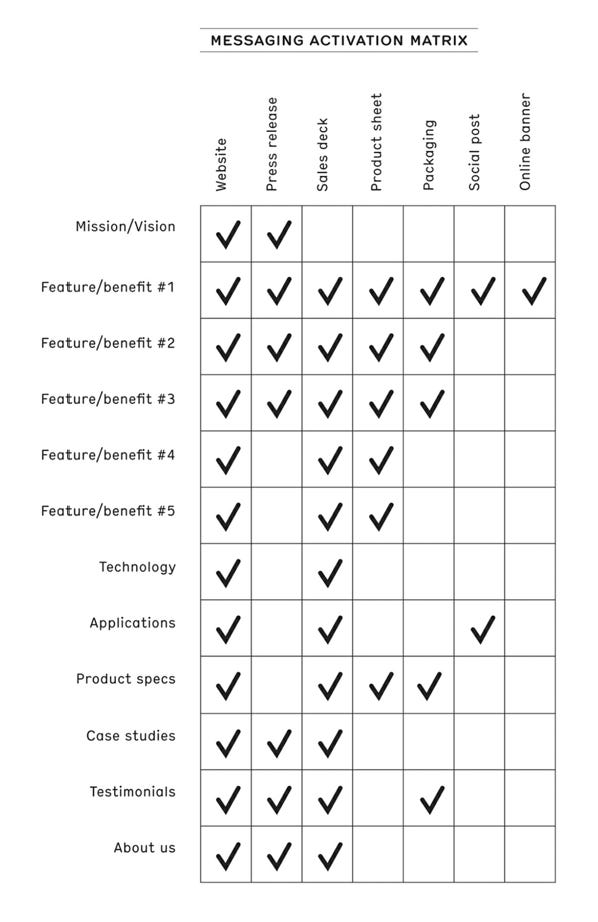

Clarify your messaging activation matrix (see example) to decide what information goes where. "Don't overwhelm or undereducate your customer as they move through multiple touchpoints along the customer journey."

Have lawyers review your marketing claims. Don’t lose trust or get hit with a class-action lawsuit due to white lies. "If you're successful, customers will always notice."

Care about the details: "An ad can’t be understood without knowing where it will appear and where it will lead to. A webpage can’t be approved until you know who will be routed to that page and what they’ll need to know and where the call to action will take them."

Invest in quality assets; you get to "amortize the hell out of them."

Expect to experiment a lot and do many things that don't work. It's the only way to figure it out and get better.

"The messaging architecture and activation matrix turned a soft art into a hard science that everyone could understand. And when everyone can understand it, they can understand how important it is."

Chapter 5.5: The Point of PMs

The role of product manager (PM) is critical for the success of your product, yet can be nebulous and misunderstood. Their most important function is to accurately represent the voice of the customer. This is translated into a) what the product should do; b) how the product should work (the spec); and c) the product messaging (facts you want customers to understand). The voice of the customer also guides the PM's collaboration with all teams to get the intent of the product brought to market. Some tips:

This is different from project manager (someone who is the voice of the project, drawing attention to potential problems); and program manager (someone who supervises groups of projects and project managers).

The role of PM is following a similar pattern as design in the 80s and 90s, going from a) unknown or nonexistent; to b) optional window dressing (to make the product look nice); to c) elevated discipline (thanks to Apple, Frog, IDEO, David Kelley), to d) understood & respected discipline. Different companies are at different stages; many are still at points (a) or (b).

Great PMs provide leverage to all teams contributing to the product's success (engineering, design, marketing, sales, support, exec).

Product management and product marketing are and should be one job, with no separation. The PM should develop and maintain the messaging matrix.

The key: build empathy for the reality of the user experience. [Story of Greg Joswiak exploring how people actually experienced the 12 hour battery life of the iPod. For many, it lasted several days.] Get good at turning what you learn into an effective narrative.

An effective PM must be a "master negotiator and communicator" because things will never go smoothly as new ideas are interjected into the process.

The PM role is hard to hire and train for. Focus on finding people who care deeply about the customer and will do whatever needs to be done to improve the product for them. (They do not need a formal technical background; a solid basic understanding of what's involved is fine.)

"This person is a needle in a haystack. An almost impossible combination of structured thinker and visionary leader, with incredible passion but also firm follow-through, who’s a vibrant people person but fascinated by technology, an incredible communicator who can work with engineering and think through marketing and not forget the business model, the economics, profitability, PR. They have to be pushy but with a smile, to know when to hold fast and when to let one slide. They’re incredibly rare. Incredibly precious. And they can and will help your business go exactly where it needs to go."

Chapter 5.6: Death of a Sales Culture

Use vested commissions to build a sales culture that aligns short-term business objectives with long-term customer relationships. This means a) making every sale a team sale (e.g. the customer success team signs off on every deal, especially helpful if you are stuck with a transaction-oriented sales org); and b) paying sales performance bonuses with stock (ideally) or the cash commission in installments over time (where the remainder is lost if the customer churns). Some tips:

Hire salespeople who put the relationship (with the customer) first, above all else.

Make sure you don't end up with distinct cultures between your company and the sales team. This will create conflict. You need people who will stick around when problems arise, not just go where the money is.

Aim to have the salesperson "stay on as a point of contact for that customer, and if there’s any kind of issue, they step in to resell them."

Emphasizing a vested commission structure is a good way to weed out the assholes. Find the people who want to be part of a real team and do right by the customers.

Chapter 5.7: Lawyer Up

Find a great (likely internal) lawyer who will help you identify risks and roadblocks and find solutions appropriate for the business. Ideally this is a lawyer who doesn't just think like a lawyer. Some tips:

If you're anywhere near successful, you'll be a target for lawsuits. Taking risks is part of building a business (just don't do anything illegal or plain stupid).

Most lawyers "live in a black-and-white world. Legal versus illegal. Defendable versus undefendable. [They] tell you the law and explain the risks. Your job is to make the decision."

The best lawyers can weigh business objectives along with their legal training to give well-reasoned advice. "A well-seasoned, experienced, and business-practical lawyer who can communicate risk effectively can be worth their weight in gold."

Identify the kinds of issues central to your business (at Nest this was IP), and find a lawyer who can provide the leadership you need as you build the product.

“Lawyers are trained to think from the competitor’s viewpoint or the government’s viewpoint or that of pissed-off customers or irate partners or suppliers or employees or investors. Then they look at what you’re working on and say, ‘Doing it this way will almost certainly get you in trouble.’ Or, on a really good day, ‘Doing it this way may turn into a lawsuit but we’ll probably be able to handle it.’”

PART VI: BE CEO

Advice on how to be successful in the unique role of CEO. [Story of his latter experience with Nest, trying to accelerate the vision by agreeing to the Google acquisition, and then hitting roadblocks.]

"People have this vision of what it’s like to be an executive or CEO or leader of a huge business unit. They assume everyone at that level has enough experience and savvy to at least appear to know what they’re doing. They assume there’s thoughtfulness and strategy and long-term thinking and reasonable deals sealed with firm handshakes. But some days, it’s high school. Some days, it’s kindergarten."

"As CEO, you spend almost all your time on people problems and communication. You’re trying to navigate a tangled web of professional relationships and intrigues, listen to but also ignore your board, maintain your company culture, buy companies or sell your own, keep people’s respect while continually pushing yourself and the team to build something great even though you barely have time to think about what you’re building anymore. It’s an extremely weird job."

Chapter 6.1: Becoming CEO

Nothing truly prepares you to be the CEO. There are three types: a) Parent CEOs (who push the team to grow and evolve); b) Babysitter CEOs (who keep things safe and predictable); and c) Incompetent CEOs (who are usually inexperienced or ill-suited to lead after the company reaches a certain size). The key: "the things you pay attention to and care about become the priorities for the company." Some tips:

You don't need to be an expert in everything; you just have to care about everything.

Expect excellence from every part of the company; you cannot casually accept mediocrity. [Example: reading the customer support articles with the same rigor as a press release.]

To achieve excellence, sometimes you need to push a little too hard. When you see it’s becoming too much for the team, "back down and find a new middle ground."

"Avoiding or ignoring any part of your company only comes back to haunt you sooner or later."

Successful leaders are: a) able to hold people and themselves accountable for results; b) hands-on but able to back-off; c) able to focus on long-term vision while diving deep into the details; d) aware of their own strengths and challenges; e) able to recognize and act according to data- vs. opinion-driven decisions; f) expert listeners (and able to adjust based on what they learn); and g) relentlessly curious.

Remember: good ideas are everywhere and may come from anyone. Especially competitors.

Your job isn't to be friends with your employees. You need to push them to be independent, thoughtful, and (ultimately) not need you to be successful. You may need to keep some emotional distance so they don’t start second-guessing your motivations.

"When you’re CEO, you’re in charge. Sure, you’re constrained by money or resources or your board, but for the first time there are no constraints on your ideas. You get to finally test out the things that other people told you couldn’t be done. It’s your opportunity to put your money where your mouth is. That freedom is thrilling and empowering and utterly terrifying. There is nothing scarier than finally getting what you want and having to take responsibility for it, good or bad. And the tables begin to turn—as CEO you can’t say “yes” to everything. You have to become the one who says “no.” Freedom is a double-edged sword. But it’s still a sword. You can use it to cut through the bullshit, the hesitation, the red tape, the habituation. You can use it to create whatever you want. The right way. Your way. You can change things. That’s why you start a company. That’s why you become CEO."

Chapter 6.2: The Board

Your board is ultimately responsible for hiring and firing the CEO (as their main way to protect the company). Otherwise, their role "comes down to giving good advice and respectful, no-bullshit feedback that hopefully steers the CEO in the right direction." Board meetings must be carefully planned and orchestrated. Some tips:

The only surprise in a board meeting should be a good surprise (like a new product prototype). Everything else should be vetted with each board member, one-on-one, prior to the meeting.

Helping the board grasp what's going on is a forcing function for the CEO to truly understand too. It’s a red flag if they ask questions about the business you can't answer without BS.

Three categories of bad boards: a) indifferent boards (often they've put you in the "future failure" bucket and are unwilling to work to help it succeed); b) dictatorial boards (often this includes the prior founder; they push the CEO into order-taking mode); or c) inexperienced boards (who don't know the business, struggle to ask hard questions, etc.)

Even the best CEO benefits from a strong board of "smart, invested, and experienced people." Likewise, consider creating a mini-board (of internal execs, other experts) for large projects within a company.

When forming a board, find: a) seed crystals (see chapter 4.2); b) investors who understand the "slog and grind of creation"; c) operators who know the challenges of building a company; d) people with specific expertise important to the success of your business.

(Optional) Consider appointing a chairperson to set the agenda, lead the meetings, and generally stay in close collaboration with the CEO. They can be a very valuable partner.

Keep your team involved (where relevant) and appropriately informed about board meetings.

"You want board members who are truly, deeply excited by what you’re making. Who can’t wait to hear what you’ve been up to. Who aren’t just there for the meetings but are with you day in and day out, helping you, finding opportunities for you to succeed. You want a board that loves your company. And that your company loves back."

Chapter 6.3: Buying and Being Bought

Most acquisitions or mergers fail due to cultural mismatches. Consider (and care about) the finer details of how your team will be incorporated into the new entity, and what advantages you gain or lose in the process (e.g. for Nest, they lost their active & experienced board of directors in the Google acquisition). Some tips:

Even when you meticulously plan out everything, there will be things that surprise you. [Nest inadvertently alienated Google when they reassured the public they’d be independent; Google’s new finance strategy left Nest on its own.]

Be cautious with bankers: they only want to get the deal done and don't care about culture.

Don’t expect even large price tags to imply future concern over the performance of the acquisition. [Google moved on to the next shiny thing.]

When you consider buying a company, focus on what you're intending to accomplish: "do you want to buy a team? Technology? Patents? Product? Customer base? Business (that is, revenue)? A brand? Some other strategic assets?" Let that guide you accordingly.

Be wary of a company trying too hard to be acquired. As Bill Campbell said, "Great companies are bought, not sold."

Be cautiously optimistic, and acknowledge you will never truly predict the future. Do the hard work and look for evidence that what you hope will come to pass actually will.

Chapter 6.4: Fuck Massages

Focus on giving your employees meaningful benefits (health insurance, 401(k), parental leave) which make a substantive impact on their lives. Perks (like massages, free clothes, gifts) will poison your culture with a sense of entitlement if you’re not careful. For a perk to be effective, it must either be a) subsidized, not free if it happens all the time (people value what they pay for); or b) rare and a surprise (if it's free). Some tips:

"If the primary way you're attracting talent is through perks, then times will absolutely get tough."

Extravagant perks hurt your bottom line and are hard to take back after people see them as their "right."

Find ways to not trap people in the office: "we rewarded employees by paying for dinner out with their families, or a weekend away. And we were happy to throw serious cash at stuff that genuinely improved people’s experience, that brought them together and exposed them to new ideas and cultures and turned coworkers into friends."

Chapter 6.5: Unbecoming CEO

Pay attention to signals it may be time to move on from your role as CEO. The main one is if you're no longer pushing the company forward and have either settled into babysitter mode yourself (or forced into it by an overly cautious board). Other circumstances are when a) the world is changing and you need someone with different experience to lead; b) or you have an awesome succession plan and you can leave on an upswing while setting up the future leaders to succeed; or c) you simply no longer like the role and are better off moving on to something else. Some tips:

Always plan ahead and make sure you have a clear and confident succession plan in place, with an executive team who can handle the company in your absence.

Sometimes resigning is the only warning flag you can wave to your team (e.g. about struggles with the parent company).

If you step down as CEO yet stay at the company, things will get messy if you’re not very careful to not undermine the new CEO every time you offer an opinion.

Anticipate a mourning period after leaving. It takes time to move on.

Conclusion: Beyond Yourself

[Author's short reflection on the meaningful relationships at the core of everything he's done, which is the most important indicator of having done something meaningful.]

Thank you! This is insanely valuable

Beast of a summary!